Our First Critique Cycle: Creating Beautiful Work through Drafts

Before diving into the far removed ancient past, I wanted to begin with students’ history. Who were they? Where had they come from? This goes back to relevance and providing a student centered approach like Slavkin speaks to in his article Engaging the Heart, Hand, Brain (2003). If we began with students’ stories, and they began to make an investment in themselves and others, maybe they wouldn’t view the people of the past that we were going to learn about in history with such indifference. By coincidence, at this time in the school year I came across a poem titled “Where I’m From” by George Ella Lyon. I thought this would be a great poem to initiate the study of history. Before studying Ancient Rome, we would tell our own story, our own “Where I’m From”. This was the first project my students took through Ron Berger’s critique cycle (2003). This poem can be accessed online at http://www.georgeellalyon.com/where.html. Because the text of this poem is challenging, filled with rich vocabulary and cultural references we spent a few days just analyzing the content of each stanza.

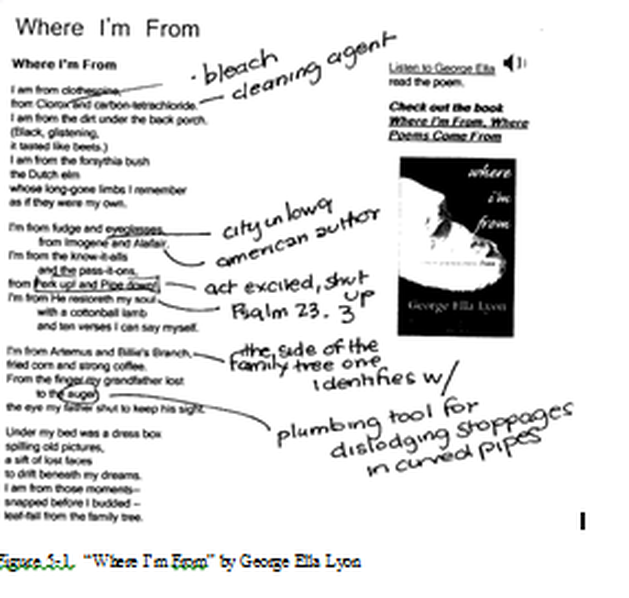

Here is the poem and the marginalia that I wrote down during our class analysis of the poem:

Before diving into the far removed ancient past, I wanted to begin with students’ history. Who were they? Where had they come from? This goes back to relevance and providing a student centered approach like Slavkin speaks to in his article Engaging the Heart, Hand, Brain (2003). If we began with students’ stories, and they began to make an investment in themselves and others, maybe they wouldn’t view the people of the past that we were going to learn about in history with such indifference. By coincidence, at this time in the school year I came across a poem titled “Where I’m From” by George Ella Lyon. I thought this would be a great poem to initiate the study of history. Before studying Ancient Rome, we would tell our own story, our own “Where I’m From”. This was the first project my students took through Ron Berger’s critique cycle (2003). This poem can be accessed online at http://www.georgeellalyon.com/where.html. Because the text of this poem is challenging, filled with rich vocabulary and cultural references we spent a few days just analyzing the content of each stanza.

Here is the poem and the marginalia that I wrote down during our class analysis of the poem:

Generating the Criteria for Beautiful Work

Next, I wanted students to generate responses to the question, “What makes a poem beautiful?” I asked students at their table groups to collaboratively brainstorm a list of the criteria on 12” by 18” white boards I had distributed to each table. I asked them what writing elements, such as repetition, did the author use? What was specifically in the poem, what was the content of it, such as references to nature? With white boards and a few colored white board markers in hand students looked at the marked up copies of their “Where I’m From,” but we also looked at Maya Angelou’s poem "Ailey, Baldwin, Floyd, Killens, and Mayfield." One of my student’s lost her grandparent the second week of school. She was out for several days. I explained to students that Angelou’s poem was one that brought me great comfort when I experienced the loss of a loved one and I shared this poem with them. We used this poem as a back-up to generate criteria for the elements that comprise a beautiful poem. White boards and markers tend to make any task more approachable and can consolidate the community around a focal point. As one table sees that another table is overflowing with ideas, they feel the pressure to do the same. It is little things like this strategy—the white board, something novel, and having students work collaboratively on a task before the whole class sets upon it, that not only help build community and a culture of expertise, but only take a few minutes. I have found that when I forget this step in my practice, (and I have—a few times this year) I am met with blank stares and a lack of participation. In these circumstances, instead of the students generating the ideas, being the community of experts, I am the one blab blab blabbing away in front of a sea of not very engaged faces.

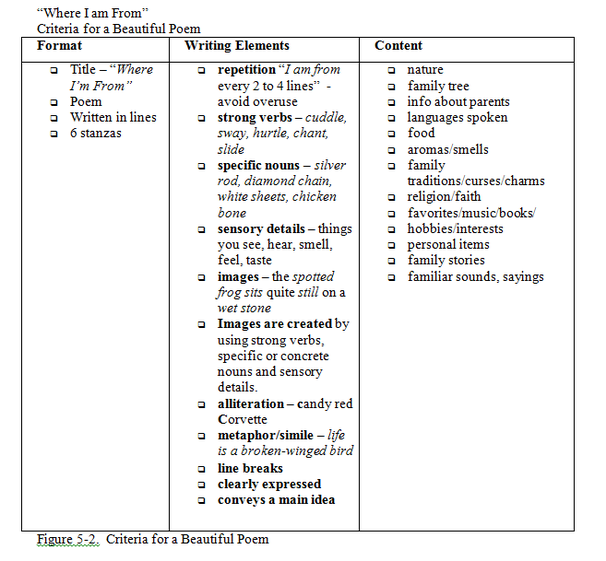

I walked the room and checked in with table groups to get a feeling of when they had exhausted their ideas. Using my computer and doc cam I projected a blank page on the screen and called on table groups to share their novel ideas about criteria for beautiful work. Novel ideas is a strategy, or protocol, that requires participants to only share a new idea that has not already been mentioned. So, it acquires acute listening skills and attentiveness to the task at hand by all participants. As students began listing ideas as a group we decided to split the criteria into “Format”, “Writing Elements” and “Content.” While students generated the criteria for each of these categories I added to the discussion by citing specific examples in italics. Below is the rubric for beautiful poetry that we generated together:

Next, I wanted students to generate responses to the question, “What makes a poem beautiful?” I asked students at their table groups to collaboratively brainstorm a list of the criteria on 12” by 18” white boards I had distributed to each table. I asked them what writing elements, such as repetition, did the author use? What was specifically in the poem, what was the content of it, such as references to nature? With white boards and a few colored white board markers in hand students looked at the marked up copies of their “Where I’m From,” but we also looked at Maya Angelou’s poem "Ailey, Baldwin, Floyd, Killens, and Mayfield." One of my student’s lost her grandparent the second week of school. She was out for several days. I explained to students that Angelou’s poem was one that brought me great comfort when I experienced the loss of a loved one and I shared this poem with them. We used this poem as a back-up to generate criteria for the elements that comprise a beautiful poem. White boards and markers tend to make any task more approachable and can consolidate the community around a focal point. As one table sees that another table is overflowing with ideas, they feel the pressure to do the same. It is little things like this strategy—the white board, something novel, and having students work collaboratively on a task before the whole class sets upon it, that not only help build community and a culture of expertise, but only take a few minutes. I have found that when I forget this step in my practice, (and I have—a few times this year) I am met with blank stares and a lack of participation. In these circumstances, instead of the students generating the ideas, being the community of experts, I am the one blab blab blabbing away in front of a sea of not very engaged faces.

I walked the room and checked in with table groups to get a feeling of when they had exhausted their ideas. Using my computer and doc cam I projected a blank page on the screen and called on table groups to share their novel ideas about criteria for beautiful work. Novel ideas is a strategy, or protocol, that requires participants to only share a new idea that has not already been mentioned. So, it acquires acute listening skills and attentiveness to the task at hand by all participants. As students began listing ideas as a group we decided to split the criteria into “Format”, “Writing Elements” and “Content.” While students generated the criteria for each of these categories I added to the discussion by citing specific examples in italics. Below is the rubric for beautiful poetry that we generated together:

With the copy of Lyon’s “Where I’m From”, analysis notes, rubric and pencil in hand, I had students write their first draft of their own “Where I’m From” poem. I’d love to report that every student happily began to write and words flowed freely and in abundance, but as any educator who has ever had experience with a class full of students and an assigned writing task knows, writing is hard work, agonizing to some, and the mere idea of committing words to paper is enough to cause paralysis. So I walked from table to table, stopping here and there to ask students questions that would help them get started. “Tell me about your family? Are you the only boy? What are some things you hear your mom say every day?” I made it a point to tell students that getting started is difficult, and that the first draft is just that, a first draft. While all of them knew that this draft was not a final, many seemed reluctant to believe this and repeatedly questioned, “This is only a rough draft, right?”

Self-Evaluating

After two days students were ready to evaluate their own first draft. In Peer Collaboration and Critique: Using Student Voices to Improve Student Work (2010) teacher Juli Ruff found that within the critique process, self-evaluation was a good strategy to use prior to peer-critique because it gave students one more opportunity to read over the work and look at the criteria they had generated for beautiful work before taking a leap of faith and handing it over to a peer for outside feedback. She writes, "In order to make them more comfortable with peer-critique, I also wanted them to have as many opportunities as possible to improve their work before they showed it to their peers." She goes on to explain, "For the evaluation of the first draft however, students reflected on their own work individually. This way they could review the class created criteria, remind themselves what they were trying to create, reinforce the criteria, and catch any mistakes before sharing with the class" (p. 22). Self-evaluation provides one more experience of safety.

I asked students to take out their first drafts and I distributed the criteria we had generated for a beautiful poem along with the following self-evaluative/reflective stems:

Here is what I did well:

Here is what I need to revise to make my poem more effective:

I think I need help on:

Questions I have for the reader of the poem (ex: Does "..." make sense?):

The room fell quiet. I walked around to the table groupings and made sure students were reading their poem and looking at the criteria. Not to my surprise, a couple of students only had the title--their ideas still waiting to be placed on paper. When I approached two separate students they prefaced me reading their poem with "I'm not a good writer," and "I don't think this is good." This reminded me of the book we read in the GSE Writing for Social Scientists (2007) by Howard S. Becker. In Chapter 1, Becker states that students use built in excuses, which he calls rituals, to ensure that what has been written could not be taken as a "finished" product. I assured them that writing was difficult for everyone and that just getting their ideas down on paper, no matter how raw, was the most important thing to do at this point.

After ten minutes or so, some students asked for clarification regarding the self-evaluative/reflective stems. "My poem doesn't have alliteration," Jennifer said. "So, do I need to add alliteration?" she asked me. Rachel asked, "In my first line I wrote, I am the first granddaughter. Does that make sense to you Mrs. Bechtel? Do you know what I mean by that?" I felt reluctant to answer their questions. Feeling the wave of my former teacher self and the "teacher knows all" perception of students about to crash down I me, I stepped back and used the discussion with students I had just had as a model for the whole class. My intent was to share that the discussion that took place could have taken place without me if students had engaged each other. At this same table, the difficulties Amy had with beginning paralleled Bob's struggle to start. If all four had discussed this with each other, perhaps I would not have been needed. Even though they had participated in planned collaborative tasks during the previous weeks of school, none of the tasks had asked so much of them—to share a personal piece of writing—one more than a paragraph long. Also, I had not yet asked them to share their poem with their peers, so they were simply relying on themselves and me.

So what next? How did I keep them from running to me? How did I get them to see their peers as resources? Going back to Juli Ruff's research, I realized that the lesson on animal drawing critique would be interesting to attempt before we moved forward to peer critique.

Imagining the Possibilities of Peer Critique

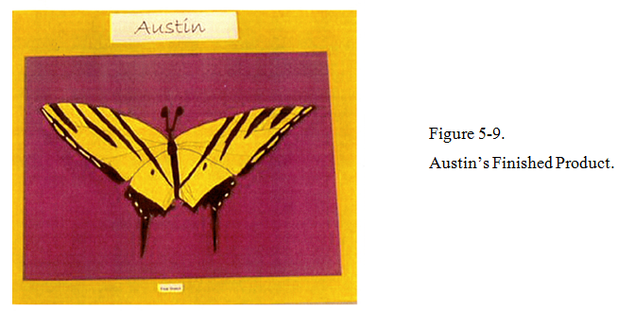

I introduced my students to the power of peer critique by showing them a series of butterfly and animal drawings that elementary students had taken through several drafts with feedback from their peers. I wanted my students to see what these youngsters had accomplished with the help of their peers, and not a single adult’s advice. Perhaps this would led them to realize that there were 33 other people in the room that could give them varying insights, perspectives and ideas on their evolving work.

Using Juli Ruff's "lesson plan" that she writes about in her book Peer Collaboration and Critique: Using Student Voices to Improve Student Work, I developed the student handout and scripted the lesson found in Appendix E and F. I first showed students the photograph that Austin, the first grader who drew the butterfly, based his butterfly on.

Self-Evaluating

After two days students were ready to evaluate their own first draft. In Peer Collaboration and Critique: Using Student Voices to Improve Student Work (2010) teacher Juli Ruff found that within the critique process, self-evaluation was a good strategy to use prior to peer-critique because it gave students one more opportunity to read over the work and look at the criteria they had generated for beautiful work before taking a leap of faith and handing it over to a peer for outside feedback. She writes, "In order to make them more comfortable with peer-critique, I also wanted them to have as many opportunities as possible to improve their work before they showed it to their peers." She goes on to explain, "For the evaluation of the first draft however, students reflected on their own work individually. This way they could review the class created criteria, remind themselves what they were trying to create, reinforce the criteria, and catch any mistakes before sharing with the class" (p. 22). Self-evaluation provides one more experience of safety.

I asked students to take out their first drafts and I distributed the criteria we had generated for a beautiful poem along with the following self-evaluative/reflective stems:

Here is what I did well:

Here is what I need to revise to make my poem more effective:

I think I need help on:

Questions I have for the reader of the poem (ex: Does "..." make sense?):

The room fell quiet. I walked around to the table groupings and made sure students were reading their poem and looking at the criteria. Not to my surprise, a couple of students only had the title--their ideas still waiting to be placed on paper. When I approached two separate students they prefaced me reading their poem with "I'm not a good writer," and "I don't think this is good." This reminded me of the book we read in the GSE Writing for Social Scientists (2007) by Howard S. Becker. In Chapter 1, Becker states that students use built in excuses, which he calls rituals, to ensure that what has been written could not be taken as a "finished" product. I assured them that writing was difficult for everyone and that just getting their ideas down on paper, no matter how raw, was the most important thing to do at this point.

After ten minutes or so, some students asked for clarification regarding the self-evaluative/reflective stems. "My poem doesn't have alliteration," Jennifer said. "So, do I need to add alliteration?" she asked me. Rachel asked, "In my first line I wrote, I am the first granddaughter. Does that make sense to you Mrs. Bechtel? Do you know what I mean by that?" I felt reluctant to answer their questions. Feeling the wave of my former teacher self and the "teacher knows all" perception of students about to crash down I me, I stepped back and used the discussion with students I had just had as a model for the whole class. My intent was to share that the discussion that took place could have taken place without me if students had engaged each other. At this same table, the difficulties Amy had with beginning paralleled Bob's struggle to start. If all four had discussed this with each other, perhaps I would not have been needed. Even though they had participated in planned collaborative tasks during the previous weeks of school, none of the tasks had asked so much of them—to share a personal piece of writing—one more than a paragraph long. Also, I had not yet asked them to share their poem with their peers, so they were simply relying on themselves and me.

So what next? How did I keep them from running to me? How did I get them to see their peers as resources? Going back to Juli Ruff's research, I realized that the lesson on animal drawing critique would be interesting to attempt before we moved forward to peer critique.

Imagining the Possibilities of Peer Critique

I introduced my students to the power of peer critique by showing them a series of butterfly and animal drawings that elementary students had taken through several drafts with feedback from their peers. I wanted my students to see what these youngsters had accomplished with the help of their peers, and not a single adult’s advice. Perhaps this would led them to realize that there were 33 other people in the room that could give them varying insights, perspectives and ideas on their evolving work.

Using Juli Ruff's "lesson plan" that she writes about in her book Peer Collaboration and Critique: Using Student Voices to Improve Student Work, I developed the student handout and scripted the lesson found in Appendix E and F. I first showed students the photograph that Austin, the first grader who drew the butterfly, based his butterfly on.

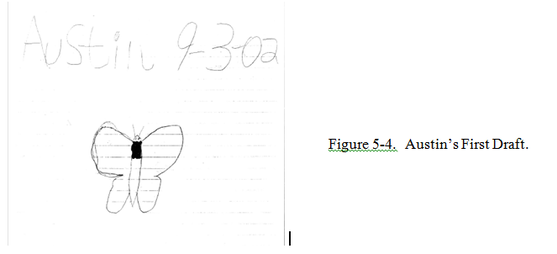

I then showed his first draft and asked students, "What feedback or advice would you give Austin so that he can improve his drawing?"

Three students commented that his draft was good for a first grader. I got the impression from their body language (pursed eyebrows, hunched shoulders) that they thought it was good enough, that in expecting more, I was expecting too much. My response was to ask the class, "What is wrong with the idea that Austin's first draft is good enough? That what he drew was good enough for a first grader, and that he could stop here?" One student commented, "It is limiting." From that point on, students gave helpful, specific feedback. Several students said that they would tell Austin to make the wings more pointy, more triangular.

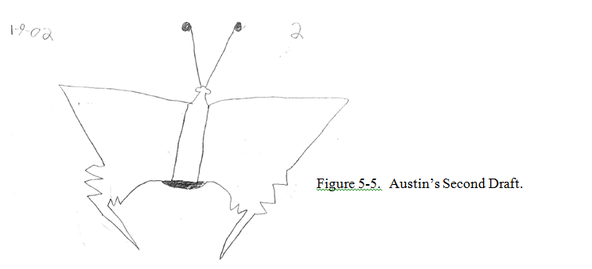

“Here is Austin’s second draft.”

“Here is Austin’s second draft.”

Audible gasps were heard in the room when the students realized that their advice about making the wings more pointy had probably been the same feedback his peers had given him based on what we saw in the second draft. They noted that in his second draft the butterfly’s body was too wide and that the lower portion of the butterflies wings, which we labeled the “tail feathers” needed to be separate from the upper portion of the wings and brought in closer together. They also believed that softer antennae would be more effective.

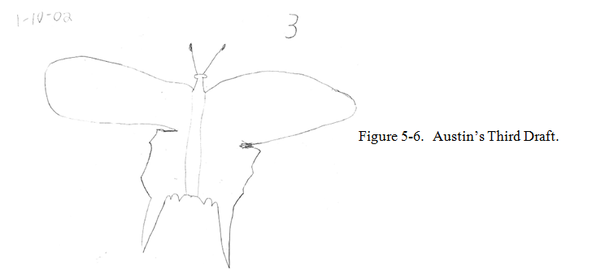

Again, when I showed Austin’s next draft, students awed that their feedback seemed to be similar to what Austin’s peer

Again, when I showed Austin’s next draft, students awed that their feedback seemed to be similar to what Austin’s peer

When I asked what advice students would give to Austin on his third draft many of the students talked to the peers at their table and I heard conversation about how the wings should be even. One student than blurted out that the wings should be symmetrical. I think this was possibly a new vocabulary word for many of my students because when I asked if they had heard the word before many nodded, but when I asked if they could define it, no one raised their hand. I told them that symmetrical meant there was a balance between the parts, between the size and shape. “Is this what you mean? Do you think the wings need to be more symmetrical?” I asked. “Yep” was the resounding response.

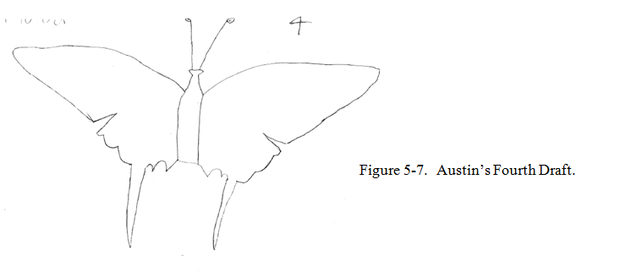

At this point many students were amazed that Austin had done four drafts. Some commented that they had never done four drafts of anything. A couple of kids asked me in semi-disbelief, “How many more are there?” When they realized that Austin did only one more draft they were quick to point out that he should add a pattern.

Realizing that a final

draft was the next step, students said Austin should add color.

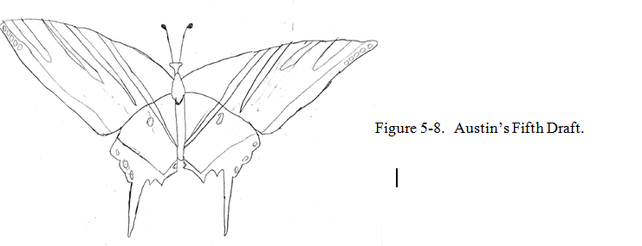

They were truly amazed at the final product. Some students commented that they were not capable of what Austin had created. I reminded them that Austin was a first grader, and that what he had done, was accomplished with the help of his peers, and not a single adult’s advice!

One of the things that struck me in this experience was the importance of vocabulary—that was the big "Aha" for me. While students used vocabulary related to insects like wings, body and pattern, they did not have the vocabulary for the decorative part of the butterflies wings. As a class we soon referred to this as "tail feathers". This lead me to the "aha" part of Juli's research and methods section that she refers to as emerging vocabulary. Students must know the vocabulary of the genre or work they are critiquing.

I wrapped up the Animal Drawing Critique with a student reflection. The majority of students in my class had not had much experience with reflection. When I gave the preliminary survey the first week of school a few students asked what reflection and evaluation meant. The questions on the reflection after looking at the animal drawings were:

Overall, students were amazed that first graders were capable of the critique that gave birth to Austin's final draft of the butterfly. Rachel and a few others commented, "Did a first grader really draw that butterfly?" Jennifer remarked, "Wow! I now question mine and others' abilities." Mika wrote, "If they could do that I could do something better." Tyson asked, "What can a seventh grader do with feedback?"

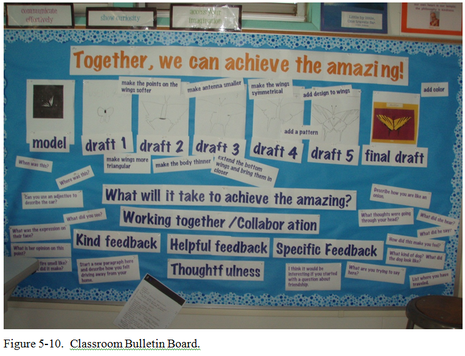

Using the animal critique photos and some of the feedback my students gave I created this bulletin board as a visual reminder of our goal—to give and seek advice that would help us accomplish beautiful work.

One of the things that struck me in this experience was the importance of vocabulary—that was the big "Aha" for me. While students used vocabulary related to insects like wings, body and pattern, they did not have the vocabulary for the decorative part of the butterflies wings. As a class we soon referred to this as "tail feathers". This lead me to the "aha" part of Juli's research and methods section that she refers to as emerging vocabulary. Students must know the vocabulary of the genre or work they are critiquing.

I wrapped up the Animal Drawing Critique with a student reflection. The majority of students in my class had not had much experience with reflection. When I gave the preliminary survey the first week of school a few students asked what reflection and evaluation meant. The questions on the reflection after looking at the animal drawings were:

- What struck you about the animal drawing critique?

- What did it take to achieve these drawings?

- What questions emerge (appear, result, grow out of, come into existence) as a result of your experience with the animal drawing critique?

- As a result of the animal drawing critique, what do you think should be our next steps as a class?

Overall, students were amazed that first graders were capable of the critique that gave birth to Austin's final draft of the butterfly. Rachel and a few others commented, "Did a first grader really draw that butterfly?" Jennifer remarked, "Wow! I now question mine and others' abilities." Mika wrote, "If they could do that I could do something better." Tyson asked, "What can a seventh grader do with feedback?"

Using the animal critique photos and some of the feedback my students gave I created this bulletin board as a visual reminder of our goal—to give and seek advice that would help us accomplish beautiful work.

Whole Class Critique of “Where I’m From”

My next step was to take a student draft of "Where I'm From" and have students apply what they had learned. Would they be able to give kind, helpful, specific feedback? I had several volunteers who wanted to share their draft and from them I chose one. I took the student’s name off of the paper and made a copy for each student. I prefaced the whole class` critique by informing the class that the student who wrote it was a classmate. I began the critique by modeling kind, helpful, specific feedback. I was impressed with the respect students showed in offering feedback. While most was kind, helpful and specific, I noticed that quite a few students said, "Be more descriptive." When I asked if this was kind and helpful many nodded yes. I then asked students, "What does be more descriptive mean'?" Only one student raised his hand. "How many of you have ever received a paper back with the comment ‘Be more descriptive’ and you weren't sure how or where to be more descriptive?” About three quarters of the class raised their hands. I then pointed out to students that asking a question about a specific point in the writer's work can help the writer be more descriptive, such as, "What is the red envelope for? What does the red envelope have to do with fireworks? Why are fireworks being set off? Is this something you do in Vietnam?"

My colleague, Mellany Parinas, suggested that one of my next steps might be a sort. The sort is a strategy where students sort a comment according to it whether helpful or unhelpful. For example, be more descriptive versus where have you traveled? This was a great warm-up before students dove into their first peer-critique with each other’s poems. The students approached it as if it were a game and when they weren’t sure if a statement was helpful or not they would discuss it with their table partners. I think the sort was a great scaffolding experience that provided students with specific examples of helpful advice. Reflecting on this now, I realize that this would be an awesome experience for students to engage in before each critique. You can find the sorting activity in Appendix G.

Peer Critique Groups

Because my students had a wide variety of writing experience, I wanted to make sure that there was at least one student in each peer critique group that had demonstrated a high level of creativity and strength in writing. Using the knowledge I had about my students’ work, their previous grades and State test scores, and their participation in class, I choose what I thought to be 9 students who would show some leadership in a peer critique group. Using a deck of cards, I gave all 9 of these students either a King, a Queen or a Jack. The remainder of the students received cards with 2 through 9. Students were then directed to form groups of 3 to 4 with one King, Queen or Jack. While I had some degree of say in the creation of critique groups, my students formed their group. Students stayed with this group through two critiques leading to the final draft.

Once students formed their peer critique groups they took out their drafts and began to read and give each other advice. I walked around the room and saw that in some groups a student was reading their poem aloud to their peers. After the poem was read, peers would pose questions and offer feedback. Most groups, however, participated in a read around and gave feedback on post-its or wrote on the actual poem. When I saw these two different modes of operation it dawned on me that I had never established norms of looking at writing or giving feedback. I felt pretty lame, but when I discussed this with students after the fact they didn’t seem to think it was such a big deal.

Giving Helpful, Specific Feedback

Teaching students how to give helpful, specific feedback is not easy. After the first critique one student, Jasper, commented on his exit card, “The easy part was reading, but the difficult part was giving feedback. It was hard because you had to give specific advice.” Another, Nikki wrote, “It was hard to find anything wrong with my partner’s poem.” And Amy wrote, “Something that was difficult was trying to figure out how to phrase what you wanted to say.” I could clearly tell from reading all of my students exit cards and reflections that giving feedback was something new to them. Students weren’t used to doing this. While statements like, “Add more description, add more detail, make it longer,” are easy for them, they admitted, that they really are not clear what these statements mean or where in their work they should do so unless it is specifically pointed out. This made me realize that giving feedback and pointing out effective qualities of work was something that I would need to emphasize and model consistently.

We took the “Where I’m From” poem through two group critique, with a few days between each critique. I believe it is important for writers to walk away and take a break from their work and come back a few days later with fresh eyes. Groups operated in the same manner as they did during the first critique, either one student reading their poem aloud followed by the group giving feedback, or, more often, the whole group participating in a read around. I wasn’t entirely pleased with the read-around as conversation about each piece seemed almost non-existent because students were commenting on the paper, not to each other. This was something I needed to change in the next critique cycle.

Amy’s “Where I’m From”

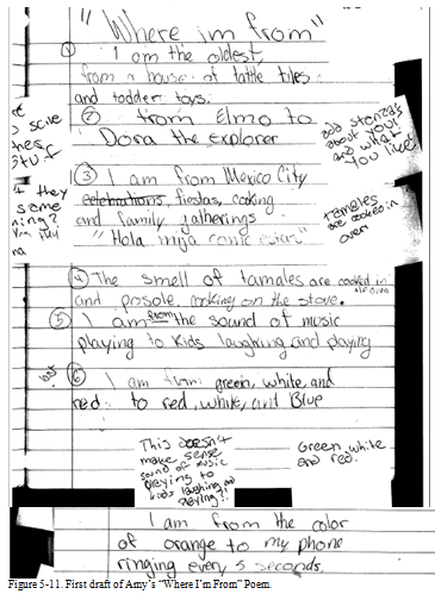

Amy was twelve years old at the beginning of the seventh grade year. She moved to San Diego from Mexico City when she was in second grade. Her primary language is Spanish and she was reclassified from being an English Language Learner in the Spring. This was Amy’s first year in a cluster class and she was enrolled in the AVID elective. Below is a series of drafts leading up to Amy’s final piece. Amy’s first draft was actually a blank piece of paper. It wasn’t until I sat down at her table and began to ask her and another focus student, Bob, who also had a blank sheet of paper, questions about their household that they both managed to get something down on paper.

My next step was to take a student draft of "Where I'm From" and have students apply what they had learned. Would they be able to give kind, helpful, specific feedback? I had several volunteers who wanted to share their draft and from them I chose one. I took the student’s name off of the paper and made a copy for each student. I prefaced the whole class` critique by informing the class that the student who wrote it was a classmate. I began the critique by modeling kind, helpful, specific feedback. I was impressed with the respect students showed in offering feedback. While most was kind, helpful and specific, I noticed that quite a few students said, "Be more descriptive." When I asked if this was kind and helpful many nodded yes. I then asked students, "What does be more descriptive mean'?" Only one student raised his hand. "How many of you have ever received a paper back with the comment ‘Be more descriptive’ and you weren't sure how or where to be more descriptive?” About three quarters of the class raised their hands. I then pointed out to students that asking a question about a specific point in the writer's work can help the writer be more descriptive, such as, "What is the red envelope for? What does the red envelope have to do with fireworks? Why are fireworks being set off? Is this something you do in Vietnam?"

My colleague, Mellany Parinas, suggested that one of my next steps might be a sort. The sort is a strategy where students sort a comment according to it whether helpful or unhelpful. For example, be more descriptive versus where have you traveled? This was a great warm-up before students dove into their first peer-critique with each other’s poems. The students approached it as if it were a game and when they weren’t sure if a statement was helpful or not they would discuss it with their table partners. I think the sort was a great scaffolding experience that provided students with specific examples of helpful advice. Reflecting on this now, I realize that this would be an awesome experience for students to engage in before each critique. You can find the sorting activity in Appendix G.

Peer Critique Groups

Because my students had a wide variety of writing experience, I wanted to make sure that there was at least one student in each peer critique group that had demonstrated a high level of creativity and strength in writing. Using the knowledge I had about my students’ work, their previous grades and State test scores, and their participation in class, I choose what I thought to be 9 students who would show some leadership in a peer critique group. Using a deck of cards, I gave all 9 of these students either a King, a Queen or a Jack. The remainder of the students received cards with 2 through 9. Students were then directed to form groups of 3 to 4 with one King, Queen or Jack. While I had some degree of say in the creation of critique groups, my students formed their group. Students stayed with this group through two critiques leading to the final draft.

Once students formed their peer critique groups they took out their drafts and began to read and give each other advice. I walked around the room and saw that in some groups a student was reading their poem aloud to their peers. After the poem was read, peers would pose questions and offer feedback. Most groups, however, participated in a read around and gave feedback on post-its or wrote on the actual poem. When I saw these two different modes of operation it dawned on me that I had never established norms of looking at writing or giving feedback. I felt pretty lame, but when I discussed this with students after the fact they didn’t seem to think it was such a big deal.

Giving Helpful, Specific Feedback

Teaching students how to give helpful, specific feedback is not easy. After the first critique one student, Jasper, commented on his exit card, “The easy part was reading, but the difficult part was giving feedback. It was hard because you had to give specific advice.” Another, Nikki wrote, “It was hard to find anything wrong with my partner’s poem.” And Amy wrote, “Something that was difficult was trying to figure out how to phrase what you wanted to say.” I could clearly tell from reading all of my students exit cards and reflections that giving feedback was something new to them. Students weren’t used to doing this. While statements like, “Add more description, add more detail, make it longer,” are easy for them, they admitted, that they really are not clear what these statements mean or where in their work they should do so unless it is specifically pointed out. This made me realize that giving feedback and pointing out effective qualities of work was something that I would need to emphasize and model consistently.

We took the “Where I’m From” poem through two group critique, with a few days between each critique. I believe it is important for writers to walk away and take a break from their work and come back a few days later with fresh eyes. Groups operated in the same manner as they did during the first critique, either one student reading their poem aloud followed by the group giving feedback, or, more often, the whole group participating in a read around. I wasn’t entirely pleased with the read-around as conversation about each piece seemed almost non-existent because students were commenting on the paper, not to each other. This was something I needed to change in the next critique cycle.

Amy’s “Where I’m From”

Amy was twelve years old at the beginning of the seventh grade year. She moved to San Diego from Mexico City when she was in second grade. Her primary language is Spanish and she was reclassified from being an English Language Learner in the Spring. This was Amy’s first year in a cluster class and she was enrolled in the AVID elective. Below is a series of drafts leading up to Amy’s final piece. Amy’s first draft was actually a blank piece of paper. It wasn’t until I sat down at her table and began to ask her and another focus student, Bob, who also had a blank sheet of paper, questions about their household that they both managed to get something down on paper.

I asked Amy and Bob to tell me about their family. Both were the eldest siblings. Amy had a young sister and talked about how she was surrounded by toys on the floor and T.V. shows made especially for younger children, like Sesame Street and Dora the Explorer. When I questioned where she was from and whether or not she traveled, she wrote the next stanza, “I am from Mexico City…” I asked her what she did at these family celebrations and she talked about food. “What kind of food do you eat?” That is when tamales and posole showed up on the paper. The post-it notes were written by Amy’s peer critique group. One of her peer’s wrote, “Tamales are cooked in the oven,” and you can see she added that to the first draft. Amy’s first draft is indeed rich in language. She used alliteration, “tattle tales” and “toddler toys”, a literary device we had generated and added to the criteria for beautiful poems. She writes specifics, such as Elmo and Dora the Explorer. She includes the smells of her family’s Mexico city celebration, “tamales in the oven” and “posole on the stove” and the sounds of music playing and kids laughing. It is a beautiful poem for a first draft.

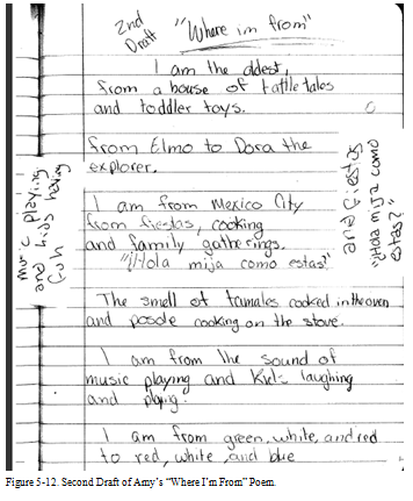

In Amy’s second draft she chose to delete celebrations and stick with the word fiestas. She added a space to create a stanza between “posole cooking on the stove” and “I am from the sound of music playing.” She did not address the advice that one of her peers wrote on a post-it during the first critique, “Add stanzas about what you like,” and she chose to ignore the post-it comment, “This doesn’t make sense the sound of music playing to kids laughing and playing.” She deleted the entire last stanza, which I thought was effective because the stanza “I am from green, white and red to red, white and blue” brings closure to the poem that the “color of orange to my phone ringing every 5 seconds” doesn’t do.

Below is Amy’s final draft. You can see she replaced “tamales cooked in the oven,” with “tamales cooked on fancy plating.” Because there are no peer notes on her second draft, we don’t know if this came about during the critique or if Amy simply made this decision on her own. What did Amy think of her final draft? On her final evaluation and reflection she wrote, “I think I earn an A because I worked really hard and I feel like it has a lot of decription.” On a scale of 1 to 4, 4 being the highest, she responded with a 4 to the statement “I am proud of my work.” Amy should be proud of her work, it gives a glimpse of who she is, a big sister who has pride in her Mexican heritage, attends family gatherings and loves food, music, laugher and playing. The specific details in her work make it beautiful.

Where I’m From

I’m the oldest

From a house of tattle tales

And toddler toys

From Elmo

To Dora the Explorer

I am from Mexico city

From fiestas, cooking

And family gatherings

“Hola mija, como estas?”

The smell of tamales cooking on fancy plating

And posole cooking on the stove

I am from the sound of music playing

And kids laughing and playing

I am from green, white and red

To red, white and blue.

-Amy

Looking at Another Student’s Process: Tyson’s “Where I’m From”

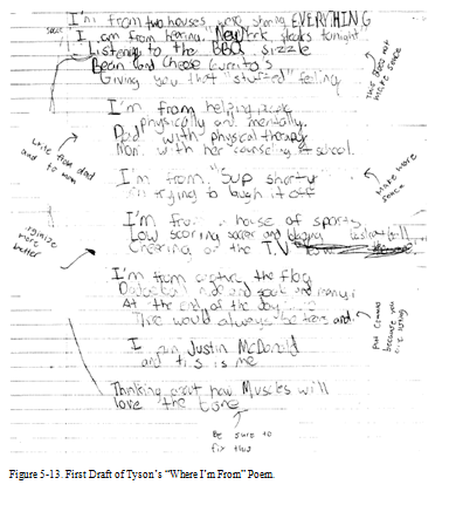

Unlike Amy, I did not see any of Tyson’s work until he turned in his final draft. Tyson was also twelve at the beginning of the seventh grade year. He was born and raised in San Diego. He had been enrolled in cluster classes since second grade and was taking A.S.B. as an elective. Here is Tyson’s first draft:

Below is Amy’s final draft. You can see she replaced “tamales cooked in the oven,” with “tamales cooked on fancy plating.” Because there are no peer notes on her second draft, we don’t know if this came about during the critique or if Amy simply made this decision on her own. What did Amy think of her final draft? On her final evaluation and reflection she wrote, “I think I earn an A because I worked really hard and I feel like it has a lot of decription.” On a scale of 1 to 4, 4 being the highest, she responded with a 4 to the statement “I am proud of my work.” Amy should be proud of her work, it gives a glimpse of who she is, a big sister who has pride in her Mexican heritage, attends family gatherings and loves food, music, laugher and playing. The specific details in her work make it beautiful.

Where I’m From

I’m the oldest

From a house of tattle tales

And toddler toys

From Elmo

To Dora the Explorer

I am from Mexico city

From fiestas, cooking

And family gatherings

“Hola mija, como estas?”

The smell of tamales cooking on fancy plating

And posole cooking on the stove

I am from the sound of music playing

And kids laughing and playing

I am from green, white and red

To red, white and blue.

-Amy

Looking at Another Student’s Process: Tyson’s “Where I’m From”

Unlike Amy, I did not see any of Tyson’s work until he turned in his final draft. Tyson was also twelve at the beginning of the seventh grade year. He was born and raised in San Diego. He had been enrolled in cluster classes since second grade and was taking A.S.B. as an elective. Here is Tyson’s first draft:

Tyson’s first draft, above, is full of rich details that reveal a lot about him, from the food that he eats to the sports that he loves. The peers in his critique group made comments like, “This doesn’t make sense”, “Organize more better”, “Put commas…”, and “Be sure to fix this.” Taken at face value, this feedback would probably be considered somewhat vague. However, when I compared Tyson’s first draft with his second draft, I wondered what the conversation was in his peer critique group that went along with these comments because there was obvious revision that corresponded to the peer feedback.

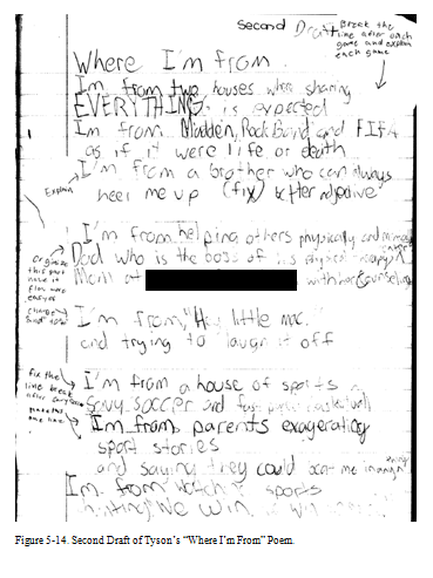

Tyson deleted the lines about food in the first stanza, replacing them with the names of video games and adding a line about his brother. His second stanza remains largely the same, with a few more details about his parents occupation. In Tyson’s third stanza he replaced “Sup shorty” with “Hey, little Cooley.” Was this in response to the peer comment “Make more sence”?

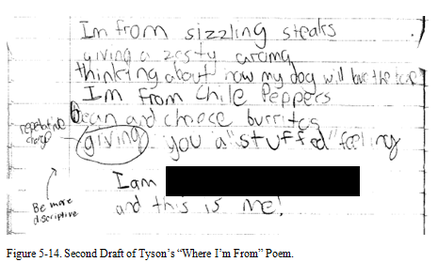

Tyson added more details along with alliteration and dialogue in his fourth stanza and omitted “At the end of the day there would always be tears…” The lines about food pop up in the fifth stanza and again he made some changes. “New York steaks” was replaced with “sizzling steaks giving a zesty aroma” and the last stanza in the first draft about Tyson’s dog, Muscles, is tied in. If you look back at the first draft you can see that a peer wrote “Be sure to fix this” and drew a line from “Thinking about how Muscles will love the bone” up to the top of the page where Tyson had written about New York steaks. I can tell that Tyson put a lot of thought into his second draft from the movement of ideas and the fine tuning and playing around he did with details, like “sizzling steak”. Below is Tyson’s second draft:

Tyson deleted the lines about food in the first stanza, replacing them with the names of video games and adding a line about his brother. His second stanza remains largely the same, with a few more details about his parents occupation. In Tyson’s third stanza he replaced “Sup shorty” with “Hey, little Cooley.” Was this in response to the peer comment “Make more sence”?

Tyson added more details along with alliteration and dialogue in his fourth stanza and omitted “At the end of the day there would always be tears…” The lines about food pop up in the fifth stanza and again he made some changes. “New York steaks” was replaced with “sizzling steaks giving a zesty aroma” and the last stanza in the first draft about Tyson’s dog, Muscles, is tied in. If you look back at the first draft you can see that a peer wrote “Be sure to fix this” and drew a line from “Thinking about how Muscles will love the bone” up to the top of the page where Tyson had written about New York steaks. I can tell that Tyson put a lot of thought into his second draft from the movement of ideas and the fine tuning and playing around he did with details, like “sizzling steak”. Below is Tyson’s second draft:

Tyson took the advice written on his second draft. He added line breaks to separate Madden football, Rock band and Fifa and “explained” or clarified the line “I’m from a brother who can always cheer me up” by replacing it with “I’m from a brother who can always change my mood with his funny antics.” In his second stanza a peer had written “Organize this part have it flow more easyer” and in reading the final draft one can see he deleted words and it does flow smoothly. Tyson completely eliminated the stanza about food and his dog anticipating the bone in his final draft. Tyson’s drafts show that he considered and usually applied the feedback he received from his peer critique group. Below is Tyson’s beautiful work, his final draft.

Where I’m From

I’m from two houses where sharing everything is expected

I’m from

Madden football

Rock band

And FIFA soccer as if it were life or death

I’m from a brother who can always change my mood with his funny antics.

I’m from helping others physically and mentally

Dad being a physical therapist

Mom being a counselor.

I’m from, “Hey, little Cooley!”

Then trying to laugh it off.

I’m from a house of sports

Savvy soccer

and fast paced basketball.

I’m from parents exaggerating sports stories

Saying that their generation could smother mine

I’m from watching sports on T.V.

Chanting, “We win, we win, we win.”

I’m Tyson Cooley

and this is me!

Whole Class Evaluation of the Critique Process

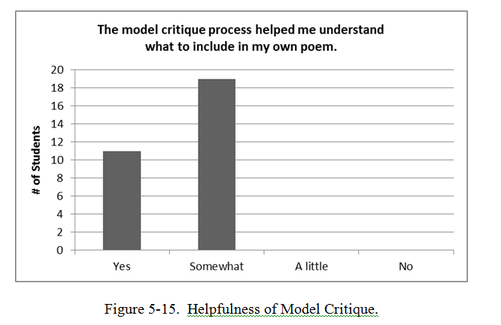

Overall students found their first experience with the critique process helpful and were proud of their final products. I gave the whole class a survey after they had completed their final drafts.

The results are below:

Where I’m From

I’m from two houses where sharing everything is expected

I’m from

Madden football

Rock band

And FIFA soccer as if it were life or death

I’m from a brother who can always change my mood with his funny antics.

I’m from helping others physically and mentally

Dad being a physical therapist

Mom being a counselor.

I’m from, “Hey, little Cooley!”

Then trying to laugh it off.

I’m from a house of sports

Savvy soccer

and fast paced basketball.

I’m from parents exaggerating sports stories

Saying that their generation could smother mine

I’m from watching sports on T.V.

Chanting, “We win, we win, we win.”

I’m Tyson Cooley

and this is me!

Whole Class Evaluation of the Critique Process

Overall students found their first experience with the critique process helpful and were proud of their final products. I gave the whole class a survey after they had completed their final drafts.

The results are below:

When asked to rate the helpfulness of the model critique, 96% of student found it helpful or somewhat helpful. The responses to this statement at first concerned me. Why had 61% of students said that the model critique “Somewhat” helped them? The purpose of the model critique was to set the standard for the work we were going to do. But I came to believe that the responses were skewed because this question was asked three weeks after we participated in the model, or instructional critique and students may have forgotten what it was.

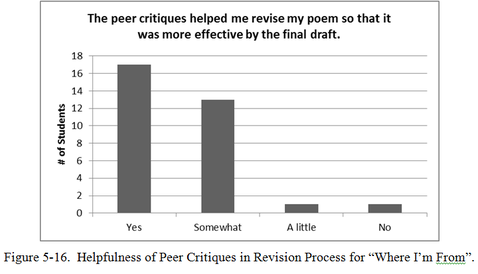

I also asked students to rate the helpfulness of the peer critiques. The majority of students, 93%, found the critique process to be somewhat to very helpful. I wondered if the two students, or 6% who did not find the critique process helpful were in groups where the students were particularly shy, or if the group was just giving the rubber stamp of approval without questioning and digging deeper to help the writer provide more details.

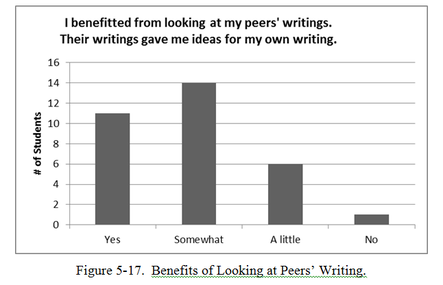

When asked if they benefitted from looking at their peer’s writings and got ideas for their own writings because of this, 78% of the class believed that they benefitted from looking at their peers work. 19% believed they benefitted to a small extent and one student believed that he/she did not benefit at all. While I was thrilled that so many students saw the value of looking at other’s work and getting ideas from it, I wondered about the 22% who said they didn’t get that much from the experience. Was looking at other students’ work for ideas something completely new to them?

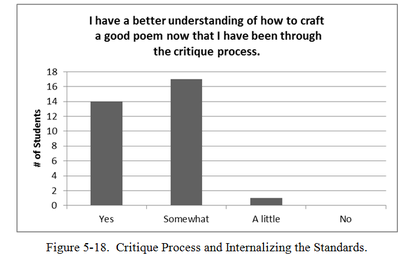

When asked if students had a better understanding of how to craft a poem based on the process they had been through, 97% of the students indicated that the critique process helped them gain a better understanding. Yes! I knew that most of my students had not written the type of poetry we had been looking at. Instead, many were familiar with Shel Silverstein and Jack Prelutsky. While both these poets are great and have written some of my favorites, the majority of my students did not realize that a poem didn’t have to rhyme. 97% stated that they understood how to craft a poem after going through the critique process. This told me that the models and the process allowed the content to sink deep and penetrate their brain. The 3%, or one student who commented, “A little”, I would have loved to talk to at the time to better understand his/her perspective. Weeks later, when I did catch up with him he said, “I don’t know why I put that.”

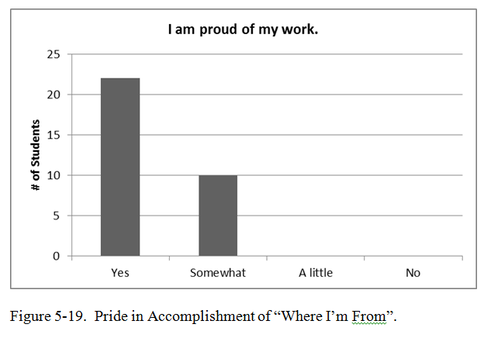

Are you proud of your work? 69% reported that they were proud of their work, but I wondered why 31% were just “Somewhat” proud. Did they want to do another round of critique? Would going back to their poem later in the year be useful? When I posed this question to the class, some of the kids said that they caught minor errors in their final draft that they didn’t see until the day of the celebration. I think that when they shared their final piece publicly, and saw the misspelled words or incorrect punctuation they were disappointed and this led to the “Somewhat” response.

Celebrating Our Work

Celebrating our poems was a smaller matter than I had anticipated. Early in my teaching career I was mentally scarred during a medieval feast when the student who had been nominated to be the classroom king, but lost in an election, threw a drumstick at the reigning king. Within a few seconds food was flying. Weeks later I was still finding food particles here and there. I vowed to never allow food in my class again. Hence, I am one of those fuddy-duddies that doesn’t like to throw parties, but loves to go to them. So, when it came to celebrating our final drafts of “Where I’m From” I was a bit gun shy, knowing that any celebration is not really a celebration without food.

Because one of the overall intents in my action research was to foster the development of a community among my students, I asked them what they would like to do to celebrate the final draft of their poem. Top down celebrations don’t always fly. As a class, students voted to bring food and share their poems with each other in small groups that extended beyond their peer critique group. They sat at tables, they sat on the floor and for an hour between bites of Rice Krispies treats, brownies, donuts and trail mix students listened to the stories of their peers and a tradition was born. What did students think about this? Jasper wrote, “The celebration made me feel free and it was important because you accomplished something and you got to share it with your friends.” Jennifer said, “It helps you overcome shyness and makes people feel good about their work.” Miranda thought, “Celebrations are important because it’s good to take a break after a few weeks of work and get rewarded for our effort.” Mika shared, “The celebrations were important because it let us share our writing with our peers and being able to see their reaction when I finished reading.”

Celebrations recognized my students for their hard work, built community among students, fostered pride in accomplishment and provided a real audience in which students could share their work. Mika’s comment about looking for the reaction of her peers when she had finished reading—that captures a valuable moment in time. She looked to her peer group for validation of her work, not me. Bob said the celebrations, “made me feel good,” and in the end that is about all that matters, isn’t it?

Celebrating a final draft was not an entirely new idea to me. Years ago after I went through a summer institute on writer’s workshop my teacher leader had indoctrinated us with the idea of publication parties. At that time I was teaching at a school in the beach area that was close to Starbucks, Einstein Bagels, Jamba Juice and some local mom and pop restaurants. With the help of parent chaperones, I would take my students to one of the local eateries and they would take turns sharing their work. Years passed, I moved schools and the Units of Inquiry were born. A scope and sequence of curriculum was mandated in English classes and I lost my groove. Students turned in their work, I graded it, and then passed it back. Passing back student work has never been a favorite activity of mine. “Why did I get this grade?” is a familiar remark.

Because students went through the process of looking at an exemplar, generating the criteria for a beautiful piece of work, and internalizing the standards through writing multiple drafts that evolved through peer feedback, I did not hear that familiar question. As shown in the survey above, students were proud of their poem. By the time their final draft was complete, students had a fairly good idea of the strengths and weaknesses of their work.

I believe that our first critique cycle was successful. The student work was beautiful, but I knew from sitting in on peer critiques and reading exit cards that some students had difficulty giving feedback. In an exit card, one student wrote, “Something that was difficult was trying to figure out how to phrase what you wanted to say.” Others voiced concerns about not getting specific feedback. So where did I go from here? What could I do to help my students learn how to give helpful, specific feedback? One of my favorite quotes is “Little by little, one travels far” by J.R.R. Tolkein. I whispered to the anxious teacher inside, “Baby steps, take baby steps” and hoped that my students would catch on. How would they catch on? Modeling. I must model, over and over, how to give feedback.

Celebrating Our Work

Celebrating our poems was a smaller matter than I had anticipated. Early in my teaching career I was mentally scarred during a medieval feast when the student who had been nominated to be the classroom king, but lost in an election, threw a drumstick at the reigning king. Within a few seconds food was flying. Weeks later I was still finding food particles here and there. I vowed to never allow food in my class again. Hence, I am one of those fuddy-duddies that doesn’t like to throw parties, but loves to go to them. So, when it came to celebrating our final drafts of “Where I’m From” I was a bit gun shy, knowing that any celebration is not really a celebration without food.

Because one of the overall intents in my action research was to foster the development of a community among my students, I asked them what they would like to do to celebrate the final draft of their poem. Top down celebrations don’t always fly. As a class, students voted to bring food and share their poems with each other in small groups that extended beyond their peer critique group. They sat at tables, they sat on the floor and for an hour between bites of Rice Krispies treats, brownies, donuts and trail mix students listened to the stories of their peers and a tradition was born. What did students think about this? Jasper wrote, “The celebration made me feel free and it was important because you accomplished something and you got to share it with your friends.” Jennifer said, “It helps you overcome shyness and makes people feel good about their work.” Miranda thought, “Celebrations are important because it’s good to take a break after a few weeks of work and get rewarded for our effort.” Mika shared, “The celebrations were important because it let us share our writing with our peers and being able to see their reaction when I finished reading.”

Celebrations recognized my students for their hard work, built community among students, fostered pride in accomplishment and provided a real audience in which students could share their work. Mika’s comment about looking for the reaction of her peers when she had finished reading—that captures a valuable moment in time. She looked to her peer group for validation of her work, not me. Bob said the celebrations, “made me feel good,” and in the end that is about all that matters, isn’t it?

Celebrating a final draft was not an entirely new idea to me. Years ago after I went through a summer institute on writer’s workshop my teacher leader had indoctrinated us with the idea of publication parties. At that time I was teaching at a school in the beach area that was close to Starbucks, Einstein Bagels, Jamba Juice and some local mom and pop restaurants. With the help of parent chaperones, I would take my students to one of the local eateries and they would take turns sharing their work. Years passed, I moved schools and the Units of Inquiry were born. A scope and sequence of curriculum was mandated in English classes and I lost my groove. Students turned in their work, I graded it, and then passed it back. Passing back student work has never been a favorite activity of mine. “Why did I get this grade?” is a familiar remark.

Because students went through the process of looking at an exemplar, generating the criteria for a beautiful piece of work, and internalizing the standards through writing multiple drafts that evolved through peer feedback, I did not hear that familiar question. As shown in the survey above, students were proud of their poem. By the time their final draft was complete, students had a fairly good idea of the strengths and weaknesses of their work.

I believe that our first critique cycle was successful. The student work was beautiful, but I knew from sitting in on peer critiques and reading exit cards that some students had difficulty giving feedback. In an exit card, one student wrote, “Something that was difficult was trying to figure out how to phrase what you wanted to say.” Others voiced concerns about not getting specific feedback. So where did I go from here? What could I do to help my students learn how to give helpful, specific feedback? One of my favorite quotes is “Little by little, one travels far” by J.R.R. Tolkein. I whispered to the anxious teacher inside, “Baby steps, take baby steps” and hoped that my students would catch on. How would they catch on? Modeling. I must model, over and over, how to give feedback.