Our Second Critique Cycle: Learning to Give Specific Feedback

With our first critique experience accomplished, we were ready for the personal soundtrack project in English. Writer and philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche once said, “Without music, life would be an error.” Music has a natural, almost innate appeal to most teenagers, if not people, I know. How about crafting an assignment that includes the music that speaks to them? Would this be a meaningful venue in which my students could also practice their narrative writing? My former students loved the personal soundtrack project so much that it showed up in almost every single student’s end of the year portfolio. Earlier in the year, when I brought up the soundtrack project with my current students the class broke out into table discussions about their favorite musicians. Their excitement was palpable.

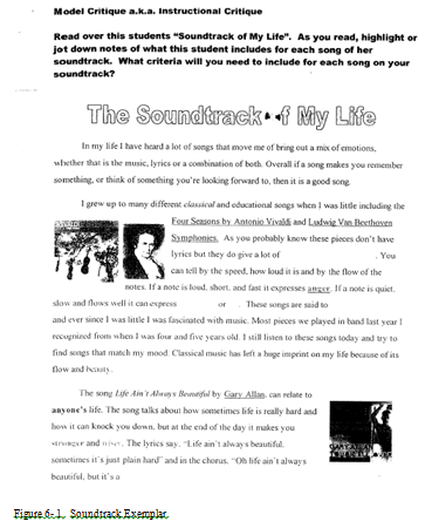

I began the Personal Soundtrack assignment with a previous student’s model. Each student had a copy of the model and I read the model aloud and I asked students to jot down what criteria they thought the student included in her soundtrack. Below is a portion of the student model we looked at:

I began the Personal Soundtrack assignment with a previous student’s model. Each student had a copy of the model and I read the model aloud and I asked students to jot down what criteria they thought the student included in her soundtrack. Below is a portion of the student model we looked at:

As I read aloud through each song on the soundtrack exemplar, I asked students to take a minute and jot down what the paragraph or paragraphs consisted of. After I saw students take some initial notes, I asked students to discuss as a table group what they noticed. I’ve learned throughout the year that when I forget this step, and attempt to solicit responses from the whole group before I give time for individual response and peer discussion, the whole class discussion is usually weak and limited to only a few participants. Building in time for students to individually digest a task, and providing them with additional time to share and build upon their findings in small groups creates a richer class dialogue. It also arms students who may have been reluctant to share their individual ideas, for a variety of reasons, with more confidence because they have attached their understanding to the groups’ understanding and in the process revised and refined it.

What my students and I discovered while reading through the model was that it had clearly identifiable criteria and it was well written. Each song on the writer’s soundtrack included a title and artist, explained the song, and used quotes effectively to support the explanation of the song or to support the writer’s personal/emotional connection to the song. The writer also used techniques, such as font size, or different fonts or colors to make specific parts of the text stand out. We could infer as readers why each song was important to the writer based on the information that was written. However, we also found that each paragraph tended to sound like it was written to fit a pattern, or answer questions. While this writer produced great work including the criteria, some of my students said it seemed like the paragraphs were set up to answer questions. This was something that I hadn’t seen before, but now, looking at it again, I kind of agreed. Eeek. After the kids left class for the day I dug through my piles of sacred salvage only to realize that the other soundtracks I had to fit the same cookie cutter mold. What now?

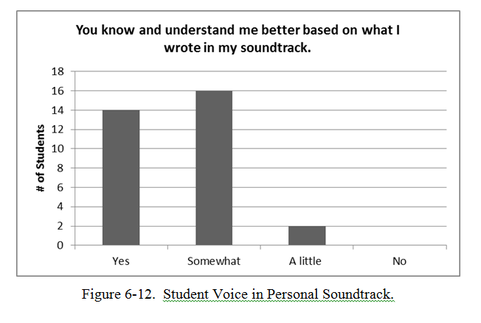

We had generated the criteria for a personal soundtrack, but how could I set forth the directions and criteria so that students did not craft an assignment that sounded like a fill in the blank? This was a HUGE dilemma, I realized, because with almost every assignment that is given a teacher runs that risk. As I thought about this, reflected on the treadmill that I had written about in my research, and visualized meaningful curriculum, I realized that what I wanted was to hear my students’ voices and for them to develop as writers with a voice, not just by following an algorithm. When I read their soundtracks, just like when I read their “Where I’m From” poems, what I wanted was to know them better. The next day, while we reviewed the criteria we had generated, I told my students that above all their goal was to get their personality on paper. I wanted to hear their voice. I wanted to read about the songs that had played an important role in their life and get to know them better as a result.

In crafting the directions to the Personal Soundtrack, I looked around the internet to see what other teachers had done with similar assignments. I needed to beef up the previous year’s directions and think about how I could support students in expressing their voice. I found some great ideas on the web, specifically one titled Soundtrack of Your Life Project 2011 - Katy ISD. I even stole this introduction from the site, “Music has become an integral part of human existence. It motivates us, calms us, inspires us, at times irritates us, and basically becomes the backdrop against which we live our lives. Songs can bring vivid memories of persons, places, and events from our own past and serve to document our thoughts, feelings, and emotions at a given time or place.” I felt like this introduction gave students so many ideas for how to connect and write about the songs in their life, whether it be that the song fired them up, soothed their weary soul, or reminded them of a special someone or place.

Building Meaning with Chalk Talk

Next, I got this idea that perhaps reading articles about music would offer students some solid evidence about music’s effects that they could incorporate in their soundtrack. Unfortunately, finding articles geared towards twelve and thirteen year olds was not as easy as I expected. I did find two articles that had some meaty ideas, Staying in Tune with Music/Impact of Music on Metal and Physical Health, by Mary A. VanDerWeele (1992) and Music on the Brain by Michael d. Lemonick (2000).

Before having students read these articles, I prepared a Chalk Talk with specific quotes that would elicit responses from students. I also included quotes about music from the web. Again, my intent was to scaffold or prepare students to craft their soundtrack with material that might cause them to think deeper, dig deeper, incorporate some of these findings into their work and avoid the cookie cutter mold.

One of the keys to an effective Chalk Talk is juicy quotes, or quotes that will trigger a response. Chalk Talk is a silent activity in which participants are directed to read and respond to quotes that speak to them. Quotes are on the white board. Every student is armed with a white board marker (I buy the multi-pack of fine felt tip markers so that white board space is optimally conserved). An alternative to this would be the use of post-its. If you do not have a classroom that has adequate white board space, you can improvise with butcher or construction paper and post the quotes on walls and desks throughout the room, and going outside is another option. The Chalk Talk Protocol is included in Appendix H. Here are some of the quotes I used in the Chalk Talk:

After silence that which comes nearest to expressing the inexpressible is music.

-Aldous Huxley

Music washes away from the soul the dust of everyday life.

-Red Auerbach

Without music, life would be an error.

-Friedrich Nietzsche

A song will outlive all sermons in the memory.

-Henry Giles

I have no pleasure in any man who despises music. It is no invention of ours: it is a gift of God. I place it next to theology. Satan hates music: he knows how it drives the evil spirit out of us.

-Martin Luther

Music is what feelings sound like.

-Anonymous

Words make you think a thought. Music makes you feel a feeling. A song makes you feel a thought

-E.Y. Harburg

Music is the universal language of mankind.

-Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

When I hear music, I fear no danger. I am invulnerable. I see no foe. I am related to the earliest times, and to the latest.

-Henry David Thoreau

Music creates changes in metabolism, circulation, blood volume, pulse, blood pressure and our moods.

– from Staying in Tune with Music

Nearly every organ in the body responds to music.

-– from Staying in Tune with Music

A top high school runner attributed his running success partly to music. The runner gets the correct mind-set by picking the right mood music and running with it.

– from Staying in Tune with Music

Kids love Chalk Talk. Why? Not particularly in this order, but…number one, they get to write on a white board with a white board marker. Number two, they get to get out their seats and walk around. And number three, they get to write what they think. During a typical school day in a traditional school those are three things that many students do not get the chance to do. In my class, I instruct students to walk around the room, read the quotes and comment on ones that “move” them. I explain that they may respond by making a connection to the quote, by rephrasing the quote and explaining what it means, or by agreeing or disagreeing with the quote and adding evidence to support their opinion. I explicitly tell students that they may not write “I agree” or “I disagree” and leave it at that. Depending on the amount of quotes, I allow eight minutes or so for students to respond. After eight minutes, I ask students to walk around again and read their peers’ comments. At this time, they are allowed to respond to their peers’ comments. I again emphasize the idea of being respectful and professional and supporting ideas with evidence. This is crucial step for an effective Chalk Talk so that those involved get to reap the benefits of the multitude of perspectives. What did my students think of Chalk Talk? Below you will find student comments I took from exit cards:

Nikki said, “I like the idea that you can choose what you want to respond to and you can express your ideas and other people can add on to them.”

Jennifer added, “Because other people don’t know who is writing what, you can express yourself without being made fun of.”

Miranda shared, “I like that in chalk talk you get to express an opinion that could persuade others to feel the way you do.”

The advantages of the Chalk Talk strategy are many. Too name a few, it fosters engagement and creates an equitable environment in which anyone and everyone can participate. Commentary is anonymous so those who are more reluctant in a discussion situation are more apt to participate. It also creates a learning situation where maximum ideas are expressed and shared in a minimal amount of time.

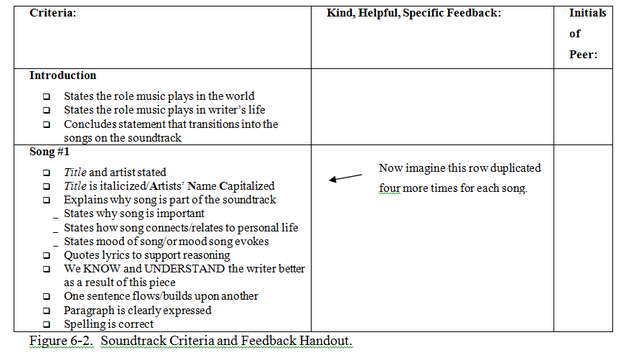

Next, it was time to distribute the directions and the criteria we had generated in the model critique. You can find the directions in Appendix I. The criteria we came up with is below:

For the Introduction of the Personal Soundtrack:

For each Song of the Personal Soundtrack

Giving Everyone a Copy

Before we launched into our first critique with students’ personal soundtracks, I reflected back on the process we went through with students’ “Where I’m From” poems. We had never established a norm of looking at each other’s work and giving feedback. In some groups, one student would read their work aloud while the other students listened. Following this, students in the group would pose questions and offer feedback. Most groups, however, participated in a read around where they read and then wrote comments on the student’s work. In retrospect, the later seemed comparable to an assembly line. While there was discussion, it was often very brief. As a teacher, I went with these models for the first cycle, and while I had a nagging feeling that there was a better way, I went with the flow. Looking back, I realize how much I had going on-- new curriculum, new students, novel combination of students, new strategies—wow, no wonder I went with the flow at that point! But now we were about to embark on our second cycle of critique and I thought that if the entire group focused on one piece of work at a time, the student whose work was being examined, would possibly get more effective feedback. I also had this feeling that once students began to ask questions about the writing and offer feedback, their ideas would trigger feedback from others in the group and a richer critique session would result. How could I facilitate this as a teacher? What would I need to do? I remembered reading something about all students having a copy of the work being discussed in DiPardo and Freedman’s research Peer Response Groups in the Writing Classroom (1988). I went back to my dangerously highlighted, flagged and annotated research articles to find where they had cited Nystrand, who:

associates group success with whether students all have photocopies of the writing under discussion. He finds that when group members both listen to a paper being read aloud and follow along on a copy of the written text, they are more likely to attend to higher order considerations (such as structure and presentation of the paper’s central argument), whereas merely listening results in more attention to lower order problems (such as word choice)(p.138).

If I was going to do this, I would need to have a due date for drafts and then spend some serious time in the copy room. It was at about this time that I remembered the hazards of copying student work: work that is written in pencil and too light, wounded thumbs and index fingers that get punctured unhinging staples, and helpless papers that get eaten by the feed tray. Thank goodness my brain was working and another thought came to me--the computer lab would be an awesome destination to word-process our first drafts. Students’ work would be legible, no one need be ashamed of their handwriting, spell check was accessible, double-spacing would allow white space for others to write feedback and students could begin to incorporate graphics and also get advice on that. I could then take their neatly word-processed, unstapled papers and put them directly in the feed tray and press COPY. It was a win-win situation. After the critique, on exit cards, I asked students what the advantages and disadvantages were of everyone in the peer critique group having a copy of each group member’s work. On the advantages:

Mika wrote, “So that we could see for ourselves and not just hear.” In other words, she got to read along as a peer read his or her work aloud.

Rachel responded, “We can all write our opinion and not be persuaded by our peers.” This is a point I had never considered. The idea that in the peer group, students might be hesitant to share feedback because of more dominant personalities or another source of pressure.

Mika also wrote on her exit card that an advantage was “We got to keep each other’s work.” When I asked her about this, she said that she asked her group members if she could keep their copies to refer to when she was revising.

What were some of the disadvantages? The number one disadvantage my students wrote about making multiple copies of each students’ drafts was that we were killing trees. Yes, I confess that I felt really guilty doing this, but I thought it served a good purpose in prompting better discussion and feedback. Thomas and Miranda brought up a similar disadvantage. Miranda wrote, “Well, the disadvantages are that the person has a lot of copies of the writing instead of one which could be easier.”

Thomas’ point seemed to connect and build on to Miranda’s, “Bringing all connections on different papers into one is a disadvantage.” I agree that the sheer amount of paper must be overwhelming for many students. As a graduate student who has gone through several critique protocols with my colleagues I understand the idea that looking at a deluge of papers with multiple perspectives and distilling them into some kind of plan for revision can be mind-boggling. At the moment, I don’t have a solution to this dilemma and think that the best way of attacking it would be to discuss it as a class during our next critique cycle by posing the question, “How do you consolidate all the ideas your peers give you into a plan of action?” This year I’ve learned I don’t have to have all the answers. I have a community of students that can help me navigate the roadblocks.

Once we made it to the lab, many students had the beginnings of their first draft in their writer’s notebooks, which are black and white composition books that I give students the first day of school. As I saw some of them open their notebooks and word-process their soundtracks I told the class that for those who already had some ideas written down, word-processing, another form of rewriting, was an ideal situation to take a second glance at their work and build upon ideas. As they reread their work, where could they be more specific, cite an example, and bring the reader into the piece?

Using “I’m Done” as an Opportunity for Whole Class Critique

It took students two to three days to write their first drafts. Take into account that while they were writing in the school’s PC lab, they were also looking over each other’s shoulder at times and sharing. One of my more gregarious and confident students, TJ, was one of the first done with his draft. He assured me half way through the second day that he was done. He had met all the criteria, he had checked twice, and assured me that he was ready for critique. I looked at his work. He had written about 5 songs that played an important role in his life. For each song he included the title, artist, a line from the song and either what the song was about or when he liked to listen to the song. He had met a lot of the criteria, but he had only written 2 to 3 sentences for each song and it lacked voice and depth. This was a great example to show my students how we could take a piece with a basic foundation and ask questions to help the writer give more information and go deeper. As I walked around the computer lab and looked at what students were writing I noticed that almost every student had similar introductions for each song, “My first song, my second song, my third song…” Just like I had done during the “Where I’m From” critique, I thought it would be a great idea to take TJ’s work through a whole class critique because it was a representative example of a first draft for a 7th grader. I hoped that the other students would take something from this and apply it to their own before we hit the critique process.

The following day I distributed TJ’s first draft and read one song at a time. After I read the first song on his soundtrack I modeled asking questions and giving feedback that would elicit more response. For the remainder of his songs, I also modeled questions that would help him delve deeper. I solicited ideas from the class too, but mostly, I was the one doing the critiquing. I think that was okay, given the fact that this process was a fairly new one and my students had written in their reflections from the “Where I’m From” critique that giving feedback was difficult. We marched back to the computer lab and finished up our first drafts.

Peer Critique Groups

I chose peer critique groups based on input students had given me on a survey after the first critique cycle with the “Where I’m From” poem. Students had input on at least one of their group members and each student had made a list of students they preferred to work with. I grouped them using their preference lists and what I knew about each student’s writing ability. Before meeting in their groups for the first critique of the personal soundtrack I set the norms for the process. This was an important step that I had left out during the first critique process with the poems. I hoped that explicitly setting these norms, along with each student having a copy of each group member’s work would facilitate authentic dialogue and feedback.

Peer Critique Norms

Even though students had a handout with the criteria we had generated for the soundtrack, the night before we met in our groups for our first critique, I felt the need to design a feedback sheet to guide students during peer critique. Here is an abbreviated version of what each student received:

What my students and I discovered while reading through the model was that it had clearly identifiable criteria and it was well written. Each song on the writer’s soundtrack included a title and artist, explained the song, and used quotes effectively to support the explanation of the song or to support the writer’s personal/emotional connection to the song. The writer also used techniques, such as font size, or different fonts or colors to make specific parts of the text stand out. We could infer as readers why each song was important to the writer based on the information that was written. However, we also found that each paragraph tended to sound like it was written to fit a pattern, or answer questions. While this writer produced great work including the criteria, some of my students said it seemed like the paragraphs were set up to answer questions. This was something that I hadn’t seen before, but now, looking at it again, I kind of agreed. Eeek. After the kids left class for the day I dug through my piles of sacred salvage only to realize that the other soundtracks I had to fit the same cookie cutter mold. What now?

We had generated the criteria for a personal soundtrack, but how could I set forth the directions and criteria so that students did not craft an assignment that sounded like a fill in the blank? This was a HUGE dilemma, I realized, because with almost every assignment that is given a teacher runs that risk. As I thought about this, reflected on the treadmill that I had written about in my research, and visualized meaningful curriculum, I realized that what I wanted was to hear my students’ voices and for them to develop as writers with a voice, not just by following an algorithm. When I read their soundtracks, just like when I read their “Where I’m From” poems, what I wanted was to know them better. The next day, while we reviewed the criteria we had generated, I told my students that above all their goal was to get their personality on paper. I wanted to hear their voice. I wanted to read about the songs that had played an important role in their life and get to know them better as a result.

In crafting the directions to the Personal Soundtrack, I looked around the internet to see what other teachers had done with similar assignments. I needed to beef up the previous year’s directions and think about how I could support students in expressing their voice. I found some great ideas on the web, specifically one titled Soundtrack of Your Life Project 2011 - Katy ISD. I even stole this introduction from the site, “Music has become an integral part of human existence. It motivates us, calms us, inspires us, at times irritates us, and basically becomes the backdrop against which we live our lives. Songs can bring vivid memories of persons, places, and events from our own past and serve to document our thoughts, feelings, and emotions at a given time or place.” I felt like this introduction gave students so many ideas for how to connect and write about the songs in their life, whether it be that the song fired them up, soothed their weary soul, or reminded them of a special someone or place.

Building Meaning with Chalk Talk

Next, I got this idea that perhaps reading articles about music would offer students some solid evidence about music’s effects that they could incorporate in their soundtrack. Unfortunately, finding articles geared towards twelve and thirteen year olds was not as easy as I expected. I did find two articles that had some meaty ideas, Staying in Tune with Music/Impact of Music on Metal and Physical Health, by Mary A. VanDerWeele (1992) and Music on the Brain by Michael d. Lemonick (2000).

Before having students read these articles, I prepared a Chalk Talk with specific quotes that would elicit responses from students. I also included quotes about music from the web. Again, my intent was to scaffold or prepare students to craft their soundtrack with material that might cause them to think deeper, dig deeper, incorporate some of these findings into their work and avoid the cookie cutter mold.

One of the keys to an effective Chalk Talk is juicy quotes, or quotes that will trigger a response. Chalk Talk is a silent activity in which participants are directed to read and respond to quotes that speak to them. Quotes are on the white board. Every student is armed with a white board marker (I buy the multi-pack of fine felt tip markers so that white board space is optimally conserved). An alternative to this would be the use of post-its. If you do not have a classroom that has adequate white board space, you can improvise with butcher or construction paper and post the quotes on walls and desks throughout the room, and going outside is another option. The Chalk Talk Protocol is included in Appendix H. Here are some of the quotes I used in the Chalk Talk:

After silence that which comes nearest to expressing the inexpressible is music.

-Aldous Huxley

Music washes away from the soul the dust of everyday life.

-Red Auerbach

Without music, life would be an error.

-Friedrich Nietzsche

A song will outlive all sermons in the memory.

-Henry Giles

I have no pleasure in any man who despises music. It is no invention of ours: it is a gift of God. I place it next to theology. Satan hates music: he knows how it drives the evil spirit out of us.

-Martin Luther

Music is what feelings sound like.

-Anonymous

Words make you think a thought. Music makes you feel a feeling. A song makes you feel a thought

-E.Y. Harburg

Music is the universal language of mankind.

-Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

When I hear music, I fear no danger. I am invulnerable. I see no foe. I am related to the earliest times, and to the latest.

-Henry David Thoreau

Music creates changes in metabolism, circulation, blood volume, pulse, blood pressure and our moods.

– from Staying in Tune with Music

Nearly every organ in the body responds to music.

-– from Staying in Tune with Music

A top high school runner attributed his running success partly to music. The runner gets the correct mind-set by picking the right mood music and running with it.

– from Staying in Tune with Music

Kids love Chalk Talk. Why? Not particularly in this order, but…number one, they get to write on a white board with a white board marker. Number two, they get to get out their seats and walk around. And number three, they get to write what they think. During a typical school day in a traditional school those are three things that many students do not get the chance to do. In my class, I instruct students to walk around the room, read the quotes and comment on ones that “move” them. I explain that they may respond by making a connection to the quote, by rephrasing the quote and explaining what it means, or by agreeing or disagreeing with the quote and adding evidence to support their opinion. I explicitly tell students that they may not write “I agree” or “I disagree” and leave it at that. Depending on the amount of quotes, I allow eight minutes or so for students to respond. After eight minutes, I ask students to walk around again and read their peers’ comments. At this time, they are allowed to respond to their peers’ comments. I again emphasize the idea of being respectful and professional and supporting ideas with evidence. This is crucial step for an effective Chalk Talk so that those involved get to reap the benefits of the multitude of perspectives. What did my students think of Chalk Talk? Below you will find student comments I took from exit cards:

Nikki said, “I like the idea that you can choose what you want to respond to and you can express your ideas and other people can add on to them.”

Jennifer added, “Because other people don’t know who is writing what, you can express yourself without being made fun of.”

Miranda shared, “I like that in chalk talk you get to express an opinion that could persuade others to feel the way you do.”

The advantages of the Chalk Talk strategy are many. Too name a few, it fosters engagement and creates an equitable environment in which anyone and everyone can participate. Commentary is anonymous so those who are more reluctant in a discussion situation are more apt to participate. It also creates a learning situation where maximum ideas are expressed and shared in a minimal amount of time.

Next, it was time to distribute the directions and the criteria we had generated in the model critique. You can find the directions in Appendix I. The criteria we came up with is below:

For the Introduction of the Personal Soundtrack:

- States the role music plays in the world

- States the role music plays in writer’s life

- Concluding statement that transitions into the songs on the soundtrack

For each Song of the Personal Soundtrack

- Title and artist stated

- Title is italicized/Artists’ Name Capitalized

- Explains why song is part of the soundtrack

- States why song is important

- States how song connects/relates to personal life

- States mood of song/or mood song evokes

- Quotes lyrics to support reasoning

- We KNOW and UNDERSTAND the writer better as a result of this piece

- One sentence flows/builds upon another

- Paragraph is clearly expressed

- Spelling is correct

Giving Everyone a Copy

Before we launched into our first critique with students’ personal soundtracks, I reflected back on the process we went through with students’ “Where I’m From” poems. We had never established a norm of looking at each other’s work and giving feedback. In some groups, one student would read their work aloud while the other students listened. Following this, students in the group would pose questions and offer feedback. Most groups, however, participated in a read around where they read and then wrote comments on the student’s work. In retrospect, the later seemed comparable to an assembly line. While there was discussion, it was often very brief. As a teacher, I went with these models for the first cycle, and while I had a nagging feeling that there was a better way, I went with the flow. Looking back, I realize how much I had going on-- new curriculum, new students, novel combination of students, new strategies—wow, no wonder I went with the flow at that point! But now we were about to embark on our second cycle of critique and I thought that if the entire group focused on one piece of work at a time, the student whose work was being examined, would possibly get more effective feedback. I also had this feeling that once students began to ask questions about the writing and offer feedback, their ideas would trigger feedback from others in the group and a richer critique session would result. How could I facilitate this as a teacher? What would I need to do? I remembered reading something about all students having a copy of the work being discussed in DiPardo and Freedman’s research Peer Response Groups in the Writing Classroom (1988). I went back to my dangerously highlighted, flagged and annotated research articles to find where they had cited Nystrand, who:

associates group success with whether students all have photocopies of the writing under discussion. He finds that when group members both listen to a paper being read aloud and follow along on a copy of the written text, they are more likely to attend to higher order considerations (such as structure and presentation of the paper’s central argument), whereas merely listening results in more attention to lower order problems (such as word choice)(p.138).

If I was going to do this, I would need to have a due date for drafts and then spend some serious time in the copy room. It was at about this time that I remembered the hazards of copying student work: work that is written in pencil and too light, wounded thumbs and index fingers that get punctured unhinging staples, and helpless papers that get eaten by the feed tray. Thank goodness my brain was working and another thought came to me--the computer lab would be an awesome destination to word-process our first drafts. Students’ work would be legible, no one need be ashamed of their handwriting, spell check was accessible, double-spacing would allow white space for others to write feedback and students could begin to incorporate graphics and also get advice on that. I could then take their neatly word-processed, unstapled papers and put them directly in the feed tray and press COPY. It was a win-win situation. After the critique, on exit cards, I asked students what the advantages and disadvantages were of everyone in the peer critique group having a copy of each group member’s work. On the advantages:

Mika wrote, “So that we could see for ourselves and not just hear.” In other words, she got to read along as a peer read his or her work aloud.

Rachel responded, “We can all write our opinion and not be persuaded by our peers.” This is a point I had never considered. The idea that in the peer group, students might be hesitant to share feedback because of more dominant personalities or another source of pressure.

Mika also wrote on her exit card that an advantage was “We got to keep each other’s work.” When I asked her about this, she said that she asked her group members if she could keep their copies to refer to when she was revising.

What were some of the disadvantages? The number one disadvantage my students wrote about making multiple copies of each students’ drafts was that we were killing trees. Yes, I confess that I felt really guilty doing this, but I thought it served a good purpose in prompting better discussion and feedback. Thomas and Miranda brought up a similar disadvantage. Miranda wrote, “Well, the disadvantages are that the person has a lot of copies of the writing instead of one which could be easier.”

Thomas’ point seemed to connect and build on to Miranda’s, “Bringing all connections on different papers into one is a disadvantage.” I agree that the sheer amount of paper must be overwhelming for many students. As a graduate student who has gone through several critique protocols with my colleagues I understand the idea that looking at a deluge of papers with multiple perspectives and distilling them into some kind of plan for revision can be mind-boggling. At the moment, I don’t have a solution to this dilemma and think that the best way of attacking it would be to discuss it as a class during our next critique cycle by posing the question, “How do you consolidate all the ideas your peers give you into a plan of action?” This year I’ve learned I don’t have to have all the answers. I have a community of students that can help me navigate the roadblocks.

Once we made it to the lab, many students had the beginnings of their first draft in their writer’s notebooks, which are black and white composition books that I give students the first day of school. As I saw some of them open their notebooks and word-process their soundtracks I told the class that for those who already had some ideas written down, word-processing, another form of rewriting, was an ideal situation to take a second glance at their work and build upon ideas. As they reread their work, where could they be more specific, cite an example, and bring the reader into the piece?

Using “I’m Done” as an Opportunity for Whole Class Critique

It took students two to three days to write their first drafts. Take into account that while they were writing in the school’s PC lab, they were also looking over each other’s shoulder at times and sharing. One of my more gregarious and confident students, TJ, was one of the first done with his draft. He assured me half way through the second day that he was done. He had met all the criteria, he had checked twice, and assured me that he was ready for critique. I looked at his work. He had written about 5 songs that played an important role in his life. For each song he included the title, artist, a line from the song and either what the song was about or when he liked to listen to the song. He had met a lot of the criteria, but he had only written 2 to 3 sentences for each song and it lacked voice and depth. This was a great example to show my students how we could take a piece with a basic foundation and ask questions to help the writer give more information and go deeper. As I walked around the computer lab and looked at what students were writing I noticed that almost every student had similar introductions for each song, “My first song, my second song, my third song…” Just like I had done during the “Where I’m From” critique, I thought it would be a great idea to take TJ’s work through a whole class critique because it was a representative example of a first draft for a 7th grader. I hoped that the other students would take something from this and apply it to their own before we hit the critique process.

The following day I distributed TJ’s first draft and read one song at a time. After I read the first song on his soundtrack I modeled asking questions and giving feedback that would elicit more response. For the remainder of his songs, I also modeled questions that would help him delve deeper. I solicited ideas from the class too, but mostly, I was the one doing the critiquing. I think that was okay, given the fact that this process was a fairly new one and my students had written in their reflections from the “Where I’m From” critique that giving feedback was difficult. We marched back to the computer lab and finished up our first drafts.

Peer Critique Groups

I chose peer critique groups based on input students had given me on a survey after the first critique cycle with the “Where I’m From” poem. Students had input on at least one of their group members and each student had made a list of students they preferred to work with. I grouped them using their preference lists and what I knew about each student’s writing ability. Before meeting in their groups for the first critique of the personal soundtrack I set the norms for the process. This was an important step that I had left out during the first critique process with the poems. I hoped that explicitly setting these norms, along with each student having a copy of each group member’s work would facilitate authentic dialogue and feedback.

Peer Critique Norms

- Meet in group. Face each other. Rearrange tables/chairs if necessary.

- Focus on one piece of work at a time. Every student should have a copy of each group member’s work.

- Read over selected work quietly. Jot down your initial warm and cool feedback on the student’s paper.

- Then, as a group, discuss warm and cool feedback. Remember to be KIND, HELPFUL and SPECIFIC.

- Writer whose work is being critiqued should ask for clarifying questions before group moves on to next group member's work.

Even though students had a handout with the criteria we had generated for the soundtrack, the night before we met in our groups for our first critique, I felt the need to design a feedback sheet to guide students during peer critique. Here is an abbreviated version of what each student received:

At the time I designed this handout I felt that all was right in the world. However, in the morning as I stuck the original in the copy machine I hesitated at the sheer amount of print on the page and the number of pages. It really did not dawn on me until that moment that our first critique cycle was for a poem of 4-6 stanzas, and this critique was for a multi-paragraph, multi-page assignment. My lack of forethought disappointed me, and as I walked to my bungalow I thought about how students could best attack longer assignments, such as the soundtrack, and devote equitable time to each group member’s work. What I have noticed about myself this year, is that while I still panic as a teacher, after all, I have 150 students under my wing, I don’t panic as much. When in doubt, I ask my students. “Here’s my dilemma,” or “Here’s our dilemma…what are some possible ways we can work around this, through this?” Of course there are always going to be a few kids that raise their hands and say, “Let’s not do it!” But once they see that is not an option, and that you are giving them a say in the decision, they generate great ideas. Some may be unrealistic, but that provides an opportunity to learn what is realistic and what is not.

As a class, some students liked the idea of reading and giving feedback on one students draft in its entirety, while others liked the idea of students taking turns and reading about one song at a time. I introduced the idea of highlighting specific areas of the soundtrack that each writer might want advice on as we do in at the High Tech High School of Graduate Education. This method allows the writer to get helpful, specific feedback in a time efficient manner. So, before meeting in peer critique groups, students were told to reread their draft and find specific areas in their writing they wanted feedback on from their peers. Once in their groups, however, the group came to an agreement about the mode of operation they were going to follow with a copy of each student’s first draft in hand.

Not much to my surprise, the multi-page feedback sheet got pushed to the side by the majority of students. Those that were using it seemed more engaged with the handout than in discussing the writing. When I asked students to raise their hand if they wrote on the feedback sheet, less than 5 raised their hands. I felt a bit exasperated, but then reminded myself of my earlier doubts. Did I want students talking about their writing, or did I want students sitting quietly, reading each other’s work, checking off and writing comments on a paper? Teachers are often hesitant to let go and give control to the students, in my case, peer critique groups. What if they’re not on task? Is this going to amount to a waste of instructional time? Can they really give each other effective feedback? So we devise checklists, or peer feedback sheets, that can actually become hurdles. My peer feedback sheet was a hurdle, and thank goodness most students choose to ignore it. What I want when they meet with each other to seek and give advice is spontaneous, natural talk. And for the most part, as I walked the room, and sat down and observed my students at work, that is what they were doing—working. Why? Because they liked the assignment and they wanted to share their work with each other and know how and where they could make it better. DiPardo and Freedman (1988) cite similar findings about control and “editing sheets”:

Freedman (1987a) finds that the use of editing sheets correlates with a marked reduction of student-to-student talk. Such devices lessen the extent to which small groups are truly peer-run collectives and, in the most extreme case, move toward a mere parceling of tasks traditionally completed by an instructor, with students attending so closely to teacher-mandated concerns that groups no longer serve the function of providing a wider, more varied audience for student writing.

While my peer feedback sheet was not an editing sheet, there are parallels in my experience and what Freedman found. Students knew the criteria, they had generated them, and while it is helpful to review them and have them posted, I needed to trust my students and the process.

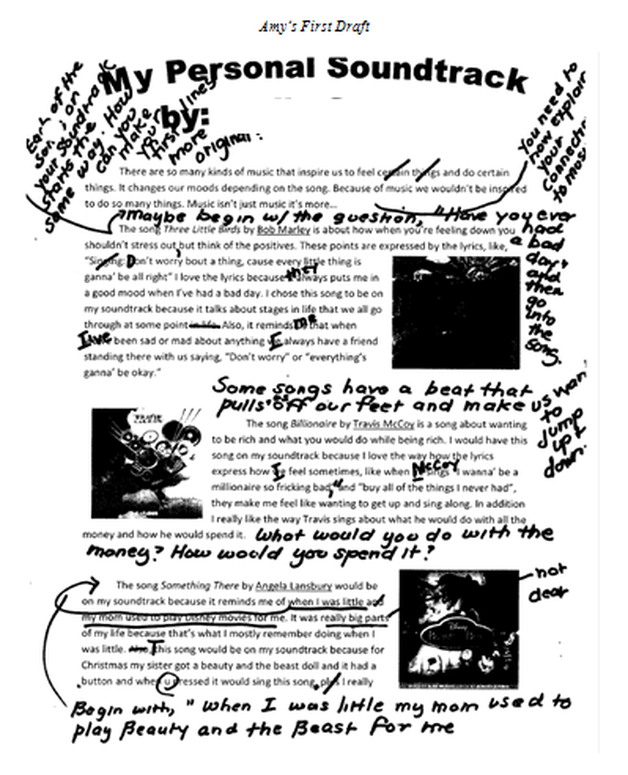

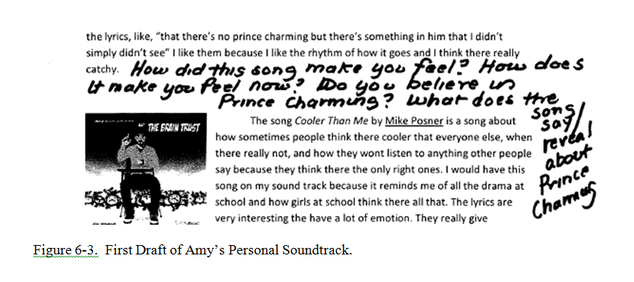

Modeling Feedback

Luckily, I had my students for a two hour block because peer critique on the personal soundtrack took the full two periods. I did not have time to give students exit cards or debrief and I wanted to do some sort of wrap up, “What are we seeing?”, “Where do we go from here?” before we went back to our first drafts and revised. The following day I took the drafts of two focus students I had worked with and given feedback and made a class set so that I could show my students what feedback might look like for the Personal Soundtrack and how to take that feedback and come up with “take-aways” to apply to the writing. Below you will find Amy’s draft. After we went through Amy’s first three songs and I discussed my comments, I asked the whole class to read her remaining songs and practice giving feedback. At the end of the period, Amy received 32 papers with her peers’ feedback for those three songs!

As a class, some students liked the idea of reading and giving feedback on one students draft in its entirety, while others liked the idea of students taking turns and reading about one song at a time. I introduced the idea of highlighting specific areas of the soundtrack that each writer might want advice on as we do in at the High Tech High School of Graduate Education. This method allows the writer to get helpful, specific feedback in a time efficient manner. So, before meeting in peer critique groups, students were told to reread their draft and find specific areas in their writing they wanted feedback on from their peers. Once in their groups, however, the group came to an agreement about the mode of operation they were going to follow with a copy of each student’s first draft in hand.

Not much to my surprise, the multi-page feedback sheet got pushed to the side by the majority of students. Those that were using it seemed more engaged with the handout than in discussing the writing. When I asked students to raise their hand if they wrote on the feedback sheet, less than 5 raised their hands. I felt a bit exasperated, but then reminded myself of my earlier doubts. Did I want students talking about their writing, or did I want students sitting quietly, reading each other’s work, checking off and writing comments on a paper? Teachers are often hesitant to let go and give control to the students, in my case, peer critique groups. What if they’re not on task? Is this going to amount to a waste of instructional time? Can they really give each other effective feedback? So we devise checklists, or peer feedback sheets, that can actually become hurdles. My peer feedback sheet was a hurdle, and thank goodness most students choose to ignore it. What I want when they meet with each other to seek and give advice is spontaneous, natural talk. And for the most part, as I walked the room, and sat down and observed my students at work, that is what they were doing—working. Why? Because they liked the assignment and they wanted to share their work with each other and know how and where they could make it better. DiPardo and Freedman (1988) cite similar findings about control and “editing sheets”:

Freedman (1987a) finds that the use of editing sheets correlates with a marked reduction of student-to-student talk. Such devices lessen the extent to which small groups are truly peer-run collectives and, in the most extreme case, move toward a mere parceling of tasks traditionally completed by an instructor, with students attending so closely to teacher-mandated concerns that groups no longer serve the function of providing a wider, more varied audience for student writing.

While my peer feedback sheet was not an editing sheet, there are parallels in my experience and what Freedman found. Students knew the criteria, they had generated them, and while it is helpful to review them and have them posted, I needed to trust my students and the process.

Modeling Feedback

Luckily, I had my students for a two hour block because peer critique on the personal soundtrack took the full two periods. I did not have time to give students exit cards or debrief and I wanted to do some sort of wrap up, “What are we seeing?”, “Where do we go from here?” before we went back to our first drafts and revised. The following day I took the drafts of two focus students I had worked with and given feedback and made a class set so that I could show my students what feedback might look like for the Personal Soundtrack and how to take that feedback and come up with “take-aways” to apply to the writing. Below you will find Amy’s draft. After we went through Amy’s first three songs and I discussed my comments, I asked the whole class to read her remaining songs and practice giving feedback. At the end of the period, Amy received 32 papers with her peers’ feedback for those three songs!

Amy had a remarkably thorough first draft. The first thing that caught our attention was that she started each song in the same manner. I asked students to refer back to a list of leads/introductions we had generated earlier in the year. The main ideas that students generated for introducing a song were to begin:

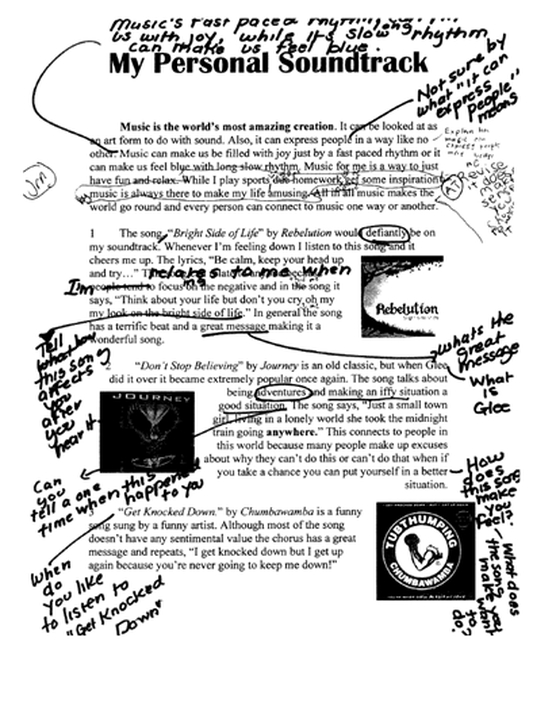

Tyson’s First Draft

You will find Tyson’s first draft below. My comments are in dark black felt tip pen, while a peer’s comments are in a lighter, fine tip pen.

- With a question that relates to the mood or lyrics of the song

- With a memory this song evokes

- With emotion/how the song makes you feel

- With an important segment of the lyrics

Tyson’s First Draft

You will find Tyson’s first draft below. My comments are in dark black felt tip pen, while a peer’s comments are in a lighter, fine tip pen.

Tyson also had an

incredibly thorough first draft. He

explained each song, but needed to be more explicit about the personal

connection he had with many of the songs.

How did the song make him feel?

How did it affect him? When did

he like to listen to this song? Could he

relate this song to a personal experience or tell us about a “one time when…”

so that we could better understand why this song was on his personal

soundtrack? Whereas Amy’s first draft

brought home the importance of catchy leads, or a hook, Tyson’s draft, like

Amy’s, once again reminded students of the importance of making a personal

connection.

In short, even though I had provided students with drafts of work that I had written feedback on, what took place was a semi- whole class critique. Based on our discussion, the feedback and what students saw the day before in peer-critique groups we came up with the following takeaways to apply to our writing:

Some ideas you could incorporate into your INTRODUCTION:

Tell us your connection/relationship with music.

How does music make you feel?

When do you listen to music?

How long have you been listening to music?

What are some of the first bands/groups/musicians/artists you remember listening to?

What would your life be like without music?

Some ideas for the INTRODUCTORY SENTENCES of each song on your soundtrack:

Þ Tell us when you typically listen to this song.

Þ Describe the mood the song puts you in. For example, ‘When I’m angry, angry like a bull with nothing but harmful intentions I listen to the song Take the Power Back by Rage Against the Machine.

Þ Take us into the scene of when you listen to this song. For example, “I’ll always remember the Tuesday night Jason Castro sang Somewhere Over the Rainbow on American Idol. I was hanging on the couch with my big brother and my mom…” or

“When I was little I was mesmerized by the Disney movie Beauty and the Beast. My mom used to play it for me and…”

Þ Ask a question that relates to the song. For example, “Have you ever had a bad day? I know I have and when I do I listen to the song Three Little Birds by Bob Marley.”

Þ Describe the beat of the song and how this affects you. For example, “Some songs have a beat that pull me off my feet and make me want to jump up and down. This is true of the song Billionaire by Travis McCoy.

Some ideas for the PARAGRAPHS of each song on your soundtrack:

Þ Avoid “you” and “us” and “we”—Put it in first person. “I”. So instead of writing music makes us want to sing or Music makes you happy make it personal—Music makes me happy.

Þ Apply how the song’s lyrics relate to you. If the song is about being famous, for example, explain if you want to be famous, or what you thing about fame.

Þ Help us understand how the song relates to an incident or a time your life by retelling a “one time when”. For example, if you’re are writing about a song you listen to when you are sad, you could include a retelling of a time when you were down and that song validated your mood and/or uplifted you.

I believe that using Amy and Tyson’s drafts to model giving feedback and generating these take-aways was a much better approach than dealing out peer feedback sheets. Why? Students had the chance to look at student models that met a lot of the criteria. They also observed and participated in giving feedback with the teacher’s guidance and modeling. Finally, as a class we reacquainted ourselves with our goals for writing and even expanded upon some of them with examples. I think that this idea, of formulating “Take-Aways” after the first peer critique is a keeper. I saw students refer back again and again to the “Take-Aways” when we hit the computer lab for revision.

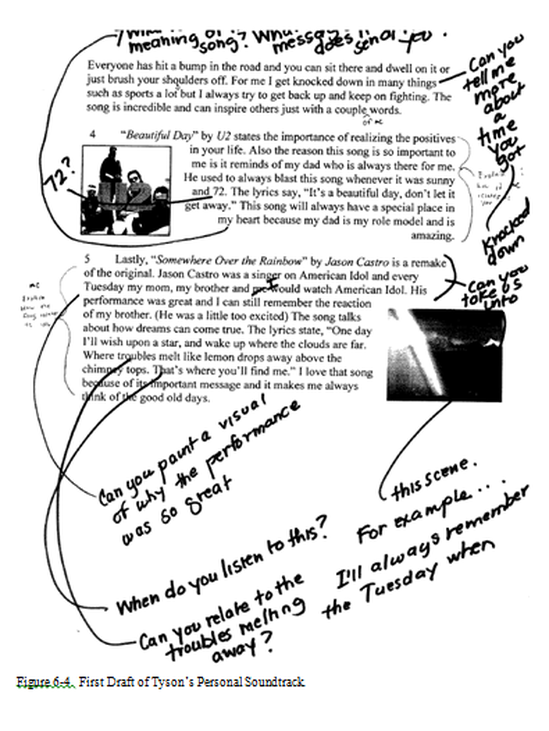

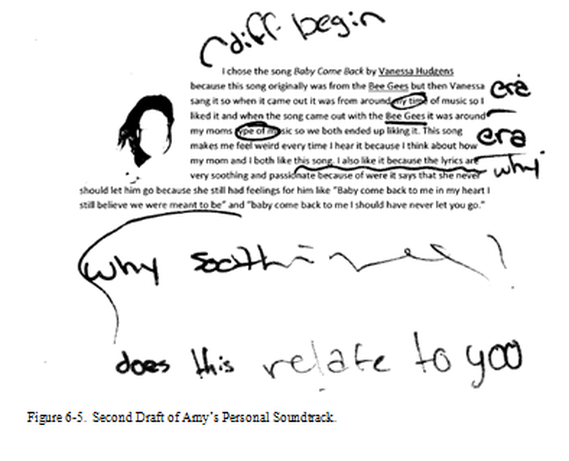

Amy’s Second Draft

In Amy’s second draft she incorporated many of the ideas I had given her. I’m really struck by the questions her peer wrote on this draft. They ask for more detail, examples and personal connections. This is the kind of feedback that will help Amy make her writing more effective—beautiful. This is the kind of feedback I would like all of my students to be able to give.

In short, even though I had provided students with drafts of work that I had written feedback on, what took place was a semi- whole class critique. Based on our discussion, the feedback and what students saw the day before in peer-critique groups we came up with the following takeaways to apply to our writing:

Some ideas you could incorporate into your INTRODUCTION:

Tell us your connection/relationship with music.

How does music make you feel?

When do you listen to music?

How long have you been listening to music?

What are some of the first bands/groups/musicians/artists you remember listening to?

What would your life be like without music?

Some ideas for the INTRODUCTORY SENTENCES of each song on your soundtrack:

Þ Tell us when you typically listen to this song.

Þ Describe the mood the song puts you in. For example, ‘When I’m angry, angry like a bull with nothing but harmful intentions I listen to the song Take the Power Back by Rage Against the Machine.

Þ Take us into the scene of when you listen to this song. For example, “I’ll always remember the Tuesday night Jason Castro sang Somewhere Over the Rainbow on American Idol. I was hanging on the couch with my big brother and my mom…” or

“When I was little I was mesmerized by the Disney movie Beauty and the Beast. My mom used to play it for me and…”

Þ Ask a question that relates to the song. For example, “Have you ever had a bad day? I know I have and when I do I listen to the song Three Little Birds by Bob Marley.”

Þ Describe the beat of the song and how this affects you. For example, “Some songs have a beat that pull me off my feet and make me want to jump up and down. This is true of the song Billionaire by Travis McCoy.

Some ideas for the PARAGRAPHS of each song on your soundtrack:

Þ Avoid “you” and “us” and “we”—Put it in first person. “I”. So instead of writing music makes us want to sing or Music makes you happy make it personal—Music makes me happy.

Þ Apply how the song’s lyrics relate to you. If the song is about being famous, for example, explain if you want to be famous, or what you thing about fame.

Þ Help us understand how the song relates to an incident or a time your life by retelling a “one time when”. For example, if you’re are writing about a song you listen to when you are sad, you could include a retelling of a time when you were down and that song validated your mood and/or uplifted you.

I believe that using Amy and Tyson’s drafts to model giving feedback and generating these take-aways was a much better approach than dealing out peer feedback sheets. Why? Students had the chance to look at student models that met a lot of the criteria. They also observed and participated in giving feedback with the teacher’s guidance and modeling. Finally, as a class we reacquainted ourselves with our goals for writing and even expanded upon some of them with examples. I think that this idea, of formulating “Take-Aways” after the first peer critique is a keeper. I saw students refer back again and again to the “Take-Aways” when we hit the computer lab for revision.

Amy’s Second Draft

In Amy’s second draft she incorporated many of the ideas I had given her. I’m really struck by the questions her peer wrote on this draft. They ask for more detail, examples and personal connections. This is the kind of feedback that will help Amy make her writing more effective—beautiful. This is the kind of feedback I would like all of my students to be able to give.

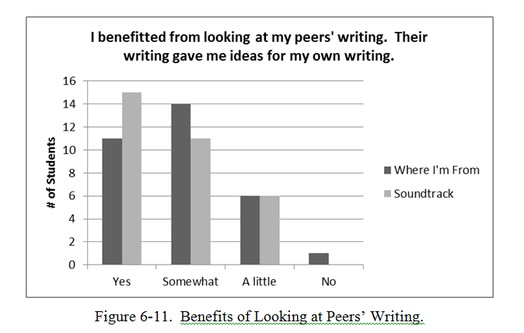

Reflecting on the Second Critique

After the second critique of the personal soundtrack I asked students to complete a reflection and survey, found in Appendix J, so I could understand how the process was going and what my next steps might be. In the first question I asked students to cite helpful/specific feedback they received from their peers. I wanted to hold students accountable for helpful and specific feedback, as this was something many were wrestling with and shared that they had difficulty giving or receiving. Were they able to recognize helpful and specific feedback? The second question asked students to write one/two things they would do to improve their personal soundtrack. This was a plan of action. I thought this was an important step for students to take in writing after they got advice. By looking at the feedback they received and turning that into one or two next steps, the revision process becomes more manageable and less abstract. I wanted students to do this right after critique so that if they had any clarifying questions to ask their peer critique group about feedback and next steps they could do it then, in class, before they packed up and all was lost. The third question was what are one/two things you saw in your peers’ soundtrack that you could incorporate into your own soundtrack? This question was equally important, because it highlighted the idea of students seeing each other as experts and resources, a part of the culture I was trying to cultivate. In hindsight, I wish I would have posted their responses to these questions on chart paper and gone over them the next day. This would have been another scaffolding opportunity for my students to incorporate other ideas into their writing. Next time.

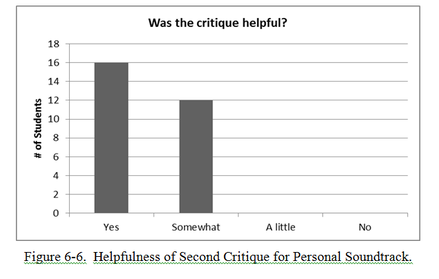

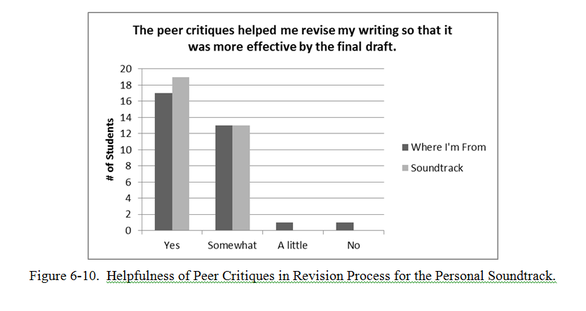

In addition to helping students articulate next steps for their own work, I wanted to get a sense of whether they still felt critique was beneficial. As you can see below, 57% of the students found it helpful and 43% of students found it somewhat helpful.

After the second critique of the personal soundtrack I asked students to complete a reflection and survey, found in Appendix J, so I could understand how the process was going and what my next steps might be. In the first question I asked students to cite helpful/specific feedback they received from their peers. I wanted to hold students accountable for helpful and specific feedback, as this was something many were wrestling with and shared that they had difficulty giving or receiving. Were they able to recognize helpful and specific feedback? The second question asked students to write one/two things they would do to improve their personal soundtrack. This was a plan of action. I thought this was an important step for students to take in writing after they got advice. By looking at the feedback they received and turning that into one or two next steps, the revision process becomes more manageable and less abstract. I wanted students to do this right after critique so that if they had any clarifying questions to ask their peer critique group about feedback and next steps they could do it then, in class, before they packed up and all was lost. The third question was what are one/two things you saw in your peers’ soundtrack that you could incorporate into your own soundtrack? This question was equally important, because it highlighted the idea of students seeing each other as experts and resources, a part of the culture I was trying to cultivate. In hindsight, I wish I would have posted their responses to these questions on chart paper and gone over them the next day. This would have been another scaffolding opportunity for my students to incorporate other ideas into their writing. Next time.

In addition to helping students articulate next steps for their own work, I wanted to get a sense of whether they still felt critique was beneficial. As you can see below, 57% of the students found it helpful and 43% of students found it somewhat helpful.

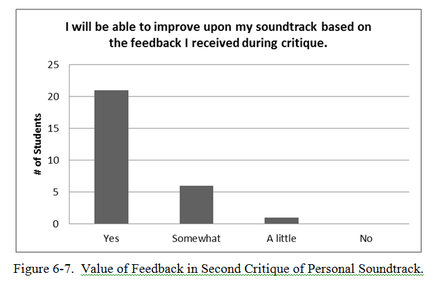

I also asked students if they would be able to improve upon their personal soundtrack based on the feedback they received from their peer critique groups. 75% of the students said they would be able to improve their soundtracks based on the feedback from their group. 21% said they would somewhat be able to improve their personal soundtrack, and 3% said they would be able to make little improvement based on feedback. These results showed me that my students were becoming more effective at giving advice.

Amy’s Final Draft

When I compare Amy’s final draft with the feedback she received from her peer, I see that she chose to ignore the questions her peer asked about the introduction and first three songs, but incorporated responses to the questions her peer asked about the last two songs. Going back and looking at these fine details makes me wonder if she thought that because I critiqued the first three songs she didn’t need to revisit these with her peer’s feedback in mind. I see their peers as viable resources. I wondered how I could make it clear to my students that while I was a teacher, I didn’t see everything. Amy also choose to take out the song I Got You Babe by UB40. When I asked Amy why she removed the song she said that it really wasn’t one of her favorites. Amy took the advice of her peer and came up with more engaging leads for Cooler Than Me and Come Back to Me. On the final draft, both of these songs read more clearly. Below you will find the songs Amy revised based on peer critique. Her entire soundtrack, which shows improvement and growth, is in Appendix K.

Have you ever met a girl/boy who thinks there too cool for you or think there all that, when they aren’t? Well, Cooler Than Me by Mike Posner is a song about that and how they won’t listen to anything other people say because they think they’re the only right one. I would have this song on my soundtrack because it reminds me of all the drama at school and how girls at school think they’re all that. The lyrics are very interesting. They have a lot of emotion. They really describe what it’s like in Middle School. My favorite part of the song is “you’ve got designer shades just to hide your face and you wear them around like your cooler than me. You never say hey or remember my name but its probably cause’ you think your cooler than me” I like these lyrics in this song because I relate to how they describe certain people at school.

Have you ever felt like you lost something you really loved but can’t have anymore? The song Come Back to Me by Vanessa Hudgens has that message in it. This song moves me and makes me feel warm because it makes me think of love and past relationships. I also like it because the lyrics are very soothing and passionate. For example, it says, “Baby come back to me in my heart I still believe. We were meant to be. Together so whatever it takes.” This means that she never should have let him go because she still has feelings for him and loves him.

Looking at Another Student’s Process

Mika’s First Draft

Mika was another one of my focus students. She was born and raised in San Diego. Like

Amy, Mika’s primary language was Spanish and she was also reclassified from being an English Language Learner this year. Mika was one of the students who was anxious to start the Personal Soundtrack project. She began her first draft in her writer’s notebook, kept many of her papers and turned them in stapled to her final draft. Although this was something all students were asked to do, I know it was a management challenge for many of them. Unlike Amy’s Soundtrack, I did not see Mika’s until the final piece was turned in. I included Mika’s work in my action research because of the amount of effort I saw her put into drafting and revision. Because English is her second language, I am aware that she spends more time crafting her work and using the right word or wording can be a challenge. Nonetheless, she is a confident student, hard worker and has high expectations for herself.

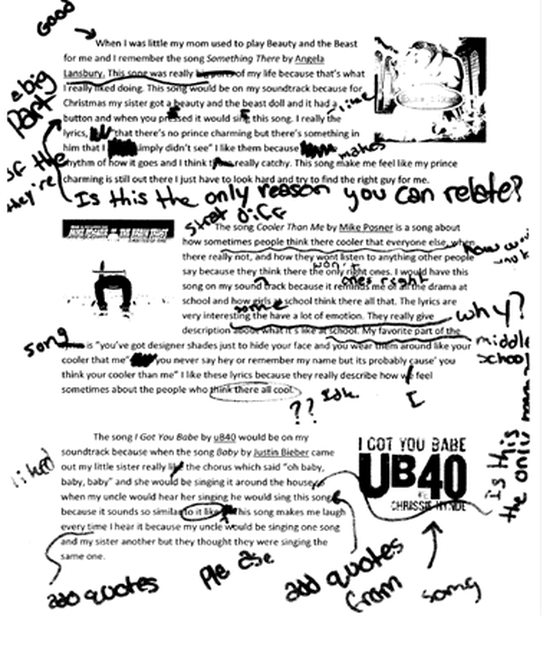

Below, you will find the first few paragraphs of Mika’s first draft:

Amy’s Final Draft

When I compare Amy’s final draft with the feedback she received from her peer, I see that she chose to ignore the questions her peer asked about the introduction and first three songs, but incorporated responses to the questions her peer asked about the last two songs. Going back and looking at these fine details makes me wonder if she thought that because I critiqued the first three songs she didn’t need to revisit these with her peer’s feedback in mind. I see their peers as viable resources. I wondered how I could make it clear to my students that while I was a teacher, I didn’t see everything. Amy also choose to take out the song I Got You Babe by UB40. When I asked Amy why she removed the song she said that it really wasn’t one of her favorites. Amy took the advice of her peer and came up with more engaging leads for Cooler Than Me and Come Back to Me. On the final draft, both of these songs read more clearly. Below you will find the songs Amy revised based on peer critique. Her entire soundtrack, which shows improvement and growth, is in Appendix K.

Have you ever met a girl/boy who thinks there too cool for you or think there all that, when they aren’t? Well, Cooler Than Me by Mike Posner is a song about that and how they won’t listen to anything other people say because they think they’re the only right one. I would have this song on my soundtrack because it reminds me of all the drama at school and how girls at school think they’re all that. The lyrics are very interesting. They have a lot of emotion. They really describe what it’s like in Middle School. My favorite part of the song is “you’ve got designer shades just to hide your face and you wear them around like your cooler than me. You never say hey or remember my name but its probably cause’ you think your cooler than me” I like these lyrics in this song because I relate to how they describe certain people at school.

Have you ever felt like you lost something you really loved but can’t have anymore? The song Come Back to Me by Vanessa Hudgens has that message in it. This song moves me and makes me feel warm because it makes me think of love and past relationships. I also like it because the lyrics are very soothing and passionate. For example, it says, “Baby come back to me in my heart I still believe. We were meant to be. Together so whatever it takes.” This means that she never should have let him go because she still has feelings for him and loves him.

Looking at Another Student’s Process

Mika’s First Draft

Mika was another one of my focus students. She was born and raised in San Diego. Like

Amy, Mika’s primary language was Spanish and she was also reclassified from being an English Language Learner this year. Mika was one of the students who was anxious to start the Personal Soundtrack project. She began her first draft in her writer’s notebook, kept many of her papers and turned them in stapled to her final draft. Although this was something all students were asked to do, I know it was a management challenge for many of them. Unlike Amy’s Soundtrack, I did not see Mika’s until the final piece was turned in. I included Mika’s work in my action research because of the amount of effort I saw her put into drafting and revision. Because English is her second language, I am aware that she spends more time crafting her work and using the right word or wording can be a challenge. Nonetheless, she is a confident student, hard worker and has high expectations for herself.

Below, you will find the first few paragraphs of Mika’s first draft:

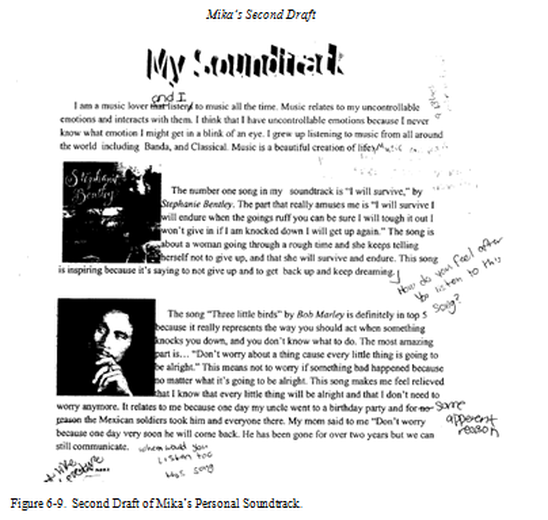

What first caught my attention on Mika’s first draft were the positive comments from her peers, such as “I love your introduction” and “I like how you explain what the song is about”. It is important for students to get validation and know that they are on the right path. I know from personal experience that this warm feedback fuels and propels writers to do the hard work of revision and wrestle with words and content. I love the feedback for “Three Little Birds” that Mika received: “I wonder if you could tell me more about this sentence” and “Why does it relate to you?” This kind of feedback helps the writer understand where they can provide more details and it makes revision feel doable. Mika applied the majority of feedback she received and moved forward on her second draft.

Looking at Mika’s second draft and the peer feedback she turned into me, I see that she didn’t get a whole lot of advice, but took most of the advice that she got. Her peers asked how she felt when she listened to the song “I Will Survive” and in her final draft she adds, “I feel unbeatable when I listen to this song.” When comparing the first, second and final drafts you can see that she continued to revise throughout. In her final copy, she added the last line to the introduction “In my opinion life without music is like a black hole.” This really struck me as a great example of voice. We really understand music’s impact on her with the sentence.

Mika’s drafts illustrate thoughtfulness and sustained effort. They show that she is listening to the feedback from her peers. I’m proud of her work. You can find Mika’s entire soundtrack in Appendix L. Below are the first few paragraphs of Mika’s final draft.

I am a music lover and I listen to music all the time. Music relates to my uncontrollable emotions and interacts with them. I think that I have uncontrollable emotions because I never know what emotion I might get in a blink of an eye. I grew up listening to music from all around the world, including Banda, and Classical (the best music). Music is a beautiful creation of life and it can make you feel a way that no other sound can. In my opinion life without music is like a black hole.

The number one song in my soundtrack is “I Will Survive” by Stephanie Bentley. The part that really inspires me is “I will survive I will endure when the goings ruff you can be sure I will tough it out I won’t give in if I am knocked down I will get up again.” The song is about a woman going through a rough time. She keeps telling herself not to give up, that she will survive and endure. This song is inspiring because it’s saying not to give up and to keep dreaming. I feel unbeatable when I listen to this song.

“Three Little Birds” by Bob Marley is definitely in my top 5 because it really represents the way you should act when something knocks you down and you don’t know what to do. The most amazing part is “Don’t worry about a thing cause every little thing is going to be alright.” This means not to worry if something bad happened because no matter what it’s going to be alright. This song makes me feel relieved. I know that every little thing will be alright and that I don’t need to worry anymore. It relates to me because one day my uncle went to a birthday party and for some apparent reason the Mexican soldiers took him and everyone there. My mom said to me, “Don’t worry because one day very soon he will come back.” He has been gone for over two years.

Celebrating Our Personal Soundtracks

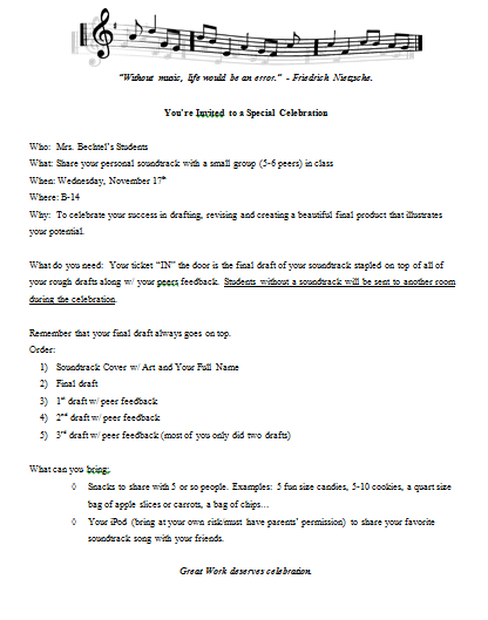

While students were revising their second draft I asked them how they wanted to celebrate the final draft of their Personal Soundtracks. Using the small, portable white boards I asked students to first generate ideas with their table partners. After 8 minutes or so, students shared their ideas. We agreed upon a celebration similar to our first celebration with the “Where I’m From” poems where each student brought yummy treats to share with others, but because this was a soundtrack, the kids wanted to bring their iPods and MP3 players so they could listen to songs. Because a few of my students did not turn in their final drafts of the “Where I’m From” poems I believed it was important to include requirements for gaining admittance to the celebration on the invitation. Below is the invitation. On the day of the celebration all students had their final draft.

Mika’s drafts illustrate thoughtfulness and sustained effort. They show that she is listening to the feedback from her peers. I’m proud of her work. You can find Mika’s entire soundtrack in Appendix L. Below are the first few paragraphs of Mika’s final draft.

I am a music lover and I listen to music all the time. Music relates to my uncontrollable emotions and interacts with them. I think that I have uncontrollable emotions because I never know what emotion I might get in a blink of an eye. I grew up listening to music from all around the world, including Banda, and Classical (the best music). Music is a beautiful creation of life and it can make you feel a way that no other sound can. In my opinion life without music is like a black hole.

The number one song in my soundtrack is “I Will Survive” by Stephanie Bentley. The part that really inspires me is “I will survive I will endure when the goings ruff you can be sure I will tough it out I won’t give in if I am knocked down I will get up again.” The song is about a woman going through a rough time. She keeps telling herself not to give up, that she will survive and endure. This song is inspiring because it’s saying not to give up and to keep dreaming. I feel unbeatable when I listen to this song.

“Three Little Birds” by Bob Marley is definitely in my top 5 because it really represents the way you should act when something knocks you down and you don’t know what to do. The most amazing part is “Don’t worry about a thing cause every little thing is going to be alright.” This means not to worry if something bad happened because no matter what it’s going to be alright. This song makes me feel relieved. I know that every little thing will be alright and that I don’t need to worry anymore. It relates to me because one day my uncle went to a birthday party and for some apparent reason the Mexican soldiers took him and everyone there. My mom said to me, “Don’t worry because one day very soon he will come back.” He has been gone for over two years.

Celebrating Our Personal Soundtracks

While students were revising their second draft I asked them how they wanted to celebrate the final draft of their Personal Soundtracks. Using the small, portable white boards I asked students to first generate ideas with their table partners. After 8 minutes or so, students shared their ideas. We agreed upon a celebration similar to our first celebration with the “Where I’m From” poems where each student brought yummy treats to share with others, but because this was a soundtrack, the kids wanted to bring their iPods and MP3 players so they could listen to songs. Because a few of my students did not turn in their final drafts of the “Where I’m From” poems I believed it was important to include requirements for gaining admittance to the celebration on the invitation. Below is the invitation. On the day of the celebration all students had their final draft.

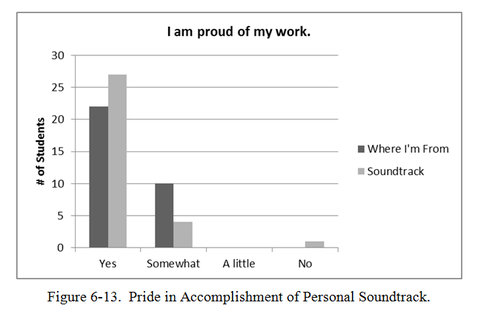

Personal Soundtrack Final Self-Evaluation

In the history of my classroom, nothing beat the soundtrack celebration. Why? Because students were allowed to bring their iPods and listen to songs from their soundtrack—something prohibited at school. For the remainder of the school year I had students attempt to persuade me that listening to music would motivate them to write, take notes or finish an assignment. Because I had a say in the formation of peer critique groups I left it to students to choose who they wanted to share their soundtrack with. Armed with treats, iPods, iPhones and their soundtracks groups spontaneously formed within a few minutes. Laughter, squeals and “That’s one of my favorites too!” filled the room. It was definitely a party, there was no hiding that. No missing iPods, iPhones or other technology were reported. Students respected the expectation I set and the trust that I conveyed to them. Because I read over soundtracks during the revision process I knew the top songs that students included. I downloaded some of these on my iPod and played them for the whole class the last 10 minutes of our celebration. After we boogied down to “Dynamite” by Taio Cruz, I had students complete a survey and final reflection. The survey results are below.

In the history of my classroom, nothing beat the soundtrack celebration. Why? Because students were allowed to bring their iPods and listen to songs from their soundtrack—something prohibited at school. For the remainder of the school year I had students attempt to persuade me that listening to music would motivate them to write, take notes or finish an assignment. Because I had a say in the formation of peer critique groups I left it to students to choose who they wanted to share their soundtrack with. Armed with treats, iPods, iPhones and their soundtracks groups spontaneously formed within a few minutes. Laughter, squeals and “That’s one of my favorites too!” filled the room. It was definitely a party, there was no hiding that. No missing iPods, iPhones or other technology were reported. Students respected the expectation I set and the trust that I conveyed to them. Because I read over soundtracks during the revision process I knew the top songs that students included. I downloaded some of these on my iPod and played them for the whole class the last 10 minutes of our celebration. After we boogied down to “Dynamite” by Taio Cruz, I had students complete a survey and final reflection. The survey results are below.