School Setting

I teach at Gaspar de Portola Middle School, one of twenty-four public middle schools in the San Diego Unified School District. Located in the community of Tierrasanta, De Portola opened its doors in 1986. De Portola serves roughly 1020 students in grades six through eight and employs forty-four teachers. The school’s enrollment is based on an “open boundary” policy with the other neighborhood middle school, Jean Farb. This means anyone in Tierrasanta or the neighboring Murphy Canyon area can attend either school if they fill out the preference letter on time. Besides resident students, de Portola admits students based on their Voluntary Ethnic Enrollment Program, or Veep, and Program Improvement School status. Students with a sibling at the school are given priority over other applicants.

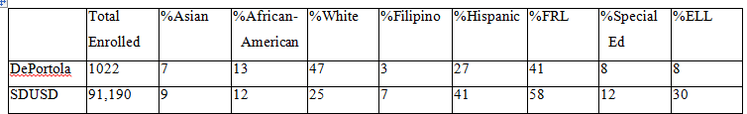

The demographics of De Portola are changing every year. While De Portola mirrors the district’s overall percentage of Asian and African American students, the white population is almost double that of the district. In addition, de Portola has significantly less Hispanic students than the district and this is evident in the English Language Learner percentage. Roughly 40% of the student population comes from military families. This specific population’s transient nature affects our enrollment and demographics throughout the year.

The demographics of De Portola are changing every year. While De Portola mirrors the district’s overall percentage of Asian and African American students, the white population is almost double that of the district. In addition, de Portola has significantly less Hispanic students than the district and this is evident in the English Language Learner percentage. Roughly 40% of the student population comes from military families. This specific population’s transient nature affects our enrollment and demographics throughout the year.

“De Portola strives to be a school in which staff, students, parents and community collaborate to ensure excellence in teaching and learning.” This mission statement reflects De Portola’s and the community’s shared emphasis on learning. De Portola is a California Distinguished School and a designated Taking Center Stage School to Watch Model Middle School. Many of de Portola’s teachers have been recognized locally and nationally for their expertise. Five teachers were district finalists for the district’s Teacher of the Year. A history teacher was a Wal•Mart Teacher of the Year and a Walt Disney Teacher Award winner. In 2008, a teacher received the California Star Teacher Award. De Portola’s academic success, as reflected in standardized test scores, is representative of the staff’s commitment to academics and a high degree of student and parent involvement. A significant strength of the school is the community among teachers. A core group of teachers have taught at the school since its inception or shortly after. A few teachers are former de Portola student teachers or former students.

The school follows a seven period day, with period 5, after lunch, being a 25 minute silent reading and advisory period. Sixth graders at de Portola have a two-hour block of English while the students in seventh and eighth have one hour. Because of this two-hour block, sixth graders do not have an elective. De Portola offers a wide variety of electives, including Spanish, A.S.B., yearbook, band/orchestra, art, computers, gateway to technology, food science, drama and media. In addition, the school offers the AVID elective. AVID is a year long elective class offered to students to help them meet college eligibility requirements. AVID targets students who are historically underserved in college and may be low income. AVID students must have average to high test scores, a 2.8-3.5 grade point average, and show desire and determination to succeed, but may lack the resources and support to do so. The AVID curriculum focuses on writing, inquiry, collaboration and reading. As our demographics change, the elective offerings change to meet the needs of our students. For example, for years one class of AVID was offered at both seventh and eighth grade. Over the last five years, the program has doubled, and now two AVID classes are offered at both grade levels.

All classes taught at de Portola are aligned with statewide standards and focus on helping students achieve or exceed grade-level standards. Teachers have been trained to write curriculum based on backwards-design. Backwards design is an instructional design based on beginning with the end in mind. Using the backwards design model, teachers consider their objectives, what they want students to know, understand and do and then plan lessons with scaffolds in place, that will allow students to accomplish these objectives.

Traditionally, De Portola schedules students into Seminar, G.A.T.E. Cluster, General Education, Special Day and Severely Handicapped Classrooms. G.A.T.E. stands for Gifted and Talented Education. The seminar program is part of the G.A.T.E. program and is specifically designed for the highly gifted, or those who test three standards deviations above the mean in the Raven Progressive Matrices. A two hour humanities based Seminar class is offered at sixth, seventh and eighth grade. The G.A.T.E. cluster classes are a combination of certified gifted students and high achieving students. G.A.T.E. certified students are those who are in the ability range greater or equal to two standard deviations above the mean on the Raven Progressive Matrices. General Education classes are offered for those students who are not certified gifted. There are roughly 120 students with special needs and while many are mainstreamed into Seminar, G.A.T.E. Cluster and General Education classes, students’ with more severe needs are scheduled into the Special Day or Severely Handicapped classes. Special Day students are mainstreamed into some general education classes, but may have a resource period or more with a special education resource teacher.

This year, De Portola adopted a new approach to scheduling students in 6th grade. Students will be scheduled based on the G.A.T.E. Cluster Diversity Model. This model requires that 25% of the class population be certified G.A.T.E. and the remainder of students are mixed ability. This model will provide teachers with more heterogeneous groups and students with higher expectations. Because this model is in direct contrast with how De Portola has historically scheduled students, the administration believes that teachers and hesitant community members will accept it more widely if phased in one grade level at a time. However, because I am an advocate of mixed ability classrooms, and I thought that a mixed ability classroom would be the ideal setting in which to research how to cultivate a culture that values beautiful work, I was given the opportunity by my principal to teach and conduct my research in a seventh grade humanities block G.A.T.E. Cluster Diversity model class.

The Humanities Department

Historically, English and history at grades six and seven were taught as a humanities block. Concern in regards to knowledge base/expertise and multiple preps was expressed by a few teachers eight years ago and the humanities block was dismantled in the seventh grade. I had, for most of my career, taught English 8. Three years ago, I asked to have the humanities block resurrected at the seventh grade as I wanted to try something new, and I saw the block as an opportunity for seventh graders, who are tested state-wide in writing, to engage in writing across the curriculum. There are many benefits to the humanities core: students experience fewer transitions, there are fewer conflicts in homework scheduling and there is more of an opportunity to develop a sense of community in a two-hour block. Currently, I am the only humanities teacher at the seventh grade level. I have two humanities blocks.

De Portola’s English department consists of 12 teachers across the grade levels. While some English teachers in grades six through eight rely more heavily on San Diego Unified School District’s Units of Inquiry as a basis of instruction, others implement a combination of their own backwards-design units and lessons from the Units. The administration at de Portola has given teachers the latitude in using their own lesson plans or lessons from the Units of Inquiry to meet grade level standards.

The California Department of Education tests all students in eighth grade on their knowledge of ancient history, world history, and U.S. history. The history department at de Portola has created a scope and sequence for teachers to follow at each grade level. If teachers pace accordingly, students should be prepared for the STAR history testing. History teachers combine the use of their own resources, a standards based text book, Teacher’s Curriculum Institute lessons, writing to learn strategies and AVID strategies.

Classroom Setting

So where do I fit into the school setting? I teach in Outer Bungolia, otherwise known as the last flank of bungalows before the P.E. field. This is a great location for my students and I, as I encourage discussion and my students and I can be quite animated at times. My bungalow is located near the lunch court and an open grassy area and so I can easily send small groups outside to work. My classroom has always been what I consider my other home. When students enter my room I want them to feel calm and comfortable. My room is decorated with hues of blue and two-person desks are arranged into groupings of four to six students. I believe that learning is a social activity and so I set up my room to allow for communication. The walls are adorned with quotes by Martin Luther King Jr., Cesar Chavez, the Dalai Lama, Mahatma Gandhi, Robert Frost, Anne Frank, Mary Oliver and Walt Whitman. Accountable talk stems, such as “I believe, I think, I agree with,” are posted above my white board as conversational reminders to students. The bulletin boards display student work and current ideas or concepts being studied. A wood organizer in the far south-west corner houses felt-tip pens, rulers, glue sticks, colored pencils, crayons and construction paper for students to access.

When students enter my room, they can always find what we will be doing that day on the white board. I am a self-defined “organic teacher”. There is a flow to my classroom. I have never been comfortable with a prescribed routine, such as starting with Daily Oral Language, or another type of warm up. I generally begin class by greeting students, sometimes asking if anyone has something they would like to share, other times asking for a metaphorical weather report to get a feel for how individual students are doing, and what they might need help with, and then we pick up where we left off the day before. I almost always review what we did the day before and set a goal for where we are headed. I am a firm believer in backwards design and by the second month of school, alert students can generally make predictions of what will happen next instructionally based on how I have previously organized lessons. Students know that they are expected to write, discuss, share, listen, give feedback and revise their work in my class.

Unlike previous years where I taught a homogeneous group of students, the humanities core in which I conducted my research consisted of a diversity cluster. A cluster is a grouping of certified gifted and talented students and high achieving students who are not certified gifted and talented. Of the thirty-four students in my class, twelve were certified gifted and talented students. Four students were certified as English language learners, while another eleven spoke a language other than English at home, but had been reclassified as English language proficient. To get a snapshot of their abilities I looked at the previous year’s California Standards Test English language scores. Out of the thirty-four students, thirteen scored advanced, nine scored proficient and twelve students scored basic. Two of the students who scored advanced on the CST were English language learners. Two of the students who scored basic on the CST were gifted and talented certified.

Students received their class schedules on the first day of school and those who had never been scheduled into a cluster class before, but were now enrolled in mine never asked, “Why am I in a cluster class?” In fact, not one student ever brought it to my attention. The second week of school I did overhear one of my students, Mika, tell her friend, “You’re in a cluster class now, you’re going to have to think harder than that” to which they both smiled at each other.

The school follows a seven period day, with period 5, after lunch, being a 25 minute silent reading and advisory period. Sixth graders at de Portola have a two-hour block of English while the students in seventh and eighth have one hour. Because of this two-hour block, sixth graders do not have an elective. De Portola offers a wide variety of electives, including Spanish, A.S.B., yearbook, band/orchestra, art, computers, gateway to technology, food science, drama and media. In addition, the school offers the AVID elective. AVID is a year long elective class offered to students to help them meet college eligibility requirements. AVID targets students who are historically underserved in college and may be low income. AVID students must have average to high test scores, a 2.8-3.5 grade point average, and show desire and determination to succeed, but may lack the resources and support to do so. The AVID curriculum focuses on writing, inquiry, collaboration and reading. As our demographics change, the elective offerings change to meet the needs of our students. For example, for years one class of AVID was offered at both seventh and eighth grade. Over the last five years, the program has doubled, and now two AVID classes are offered at both grade levels.

All classes taught at de Portola are aligned with statewide standards and focus on helping students achieve or exceed grade-level standards. Teachers have been trained to write curriculum based on backwards-design. Backwards design is an instructional design based on beginning with the end in mind. Using the backwards design model, teachers consider their objectives, what they want students to know, understand and do and then plan lessons with scaffolds in place, that will allow students to accomplish these objectives.

Traditionally, De Portola schedules students into Seminar, G.A.T.E. Cluster, General Education, Special Day and Severely Handicapped Classrooms. G.A.T.E. stands for Gifted and Talented Education. The seminar program is part of the G.A.T.E. program and is specifically designed for the highly gifted, or those who test three standards deviations above the mean in the Raven Progressive Matrices. A two hour humanities based Seminar class is offered at sixth, seventh and eighth grade. The G.A.T.E. cluster classes are a combination of certified gifted students and high achieving students. G.A.T.E. certified students are those who are in the ability range greater or equal to two standard deviations above the mean on the Raven Progressive Matrices. General Education classes are offered for those students who are not certified gifted. There are roughly 120 students with special needs and while many are mainstreamed into Seminar, G.A.T.E. Cluster and General Education classes, students’ with more severe needs are scheduled into the Special Day or Severely Handicapped classes. Special Day students are mainstreamed into some general education classes, but may have a resource period or more with a special education resource teacher.

This year, De Portola adopted a new approach to scheduling students in 6th grade. Students will be scheduled based on the G.A.T.E. Cluster Diversity Model. This model requires that 25% of the class population be certified G.A.T.E. and the remainder of students are mixed ability. This model will provide teachers with more heterogeneous groups and students with higher expectations. Because this model is in direct contrast with how De Portola has historically scheduled students, the administration believes that teachers and hesitant community members will accept it more widely if phased in one grade level at a time. However, because I am an advocate of mixed ability classrooms, and I thought that a mixed ability classroom would be the ideal setting in which to research how to cultivate a culture that values beautiful work, I was given the opportunity by my principal to teach and conduct my research in a seventh grade humanities block G.A.T.E. Cluster Diversity model class.

The Humanities Department

Historically, English and history at grades six and seven were taught as a humanities block. Concern in regards to knowledge base/expertise and multiple preps was expressed by a few teachers eight years ago and the humanities block was dismantled in the seventh grade. I had, for most of my career, taught English 8. Three years ago, I asked to have the humanities block resurrected at the seventh grade as I wanted to try something new, and I saw the block as an opportunity for seventh graders, who are tested state-wide in writing, to engage in writing across the curriculum. There are many benefits to the humanities core: students experience fewer transitions, there are fewer conflicts in homework scheduling and there is more of an opportunity to develop a sense of community in a two-hour block. Currently, I am the only humanities teacher at the seventh grade level. I have two humanities blocks.

De Portola’s English department consists of 12 teachers across the grade levels. While some English teachers in grades six through eight rely more heavily on San Diego Unified School District’s Units of Inquiry as a basis of instruction, others implement a combination of their own backwards-design units and lessons from the Units. The administration at de Portola has given teachers the latitude in using their own lesson plans or lessons from the Units of Inquiry to meet grade level standards.

The California Department of Education tests all students in eighth grade on their knowledge of ancient history, world history, and U.S. history. The history department at de Portola has created a scope and sequence for teachers to follow at each grade level. If teachers pace accordingly, students should be prepared for the STAR history testing. History teachers combine the use of their own resources, a standards based text book, Teacher’s Curriculum Institute lessons, writing to learn strategies and AVID strategies.

Classroom Setting

So where do I fit into the school setting? I teach in Outer Bungolia, otherwise known as the last flank of bungalows before the P.E. field. This is a great location for my students and I, as I encourage discussion and my students and I can be quite animated at times. My bungalow is located near the lunch court and an open grassy area and so I can easily send small groups outside to work. My classroom has always been what I consider my other home. When students enter my room I want them to feel calm and comfortable. My room is decorated with hues of blue and two-person desks are arranged into groupings of four to six students. I believe that learning is a social activity and so I set up my room to allow for communication. The walls are adorned with quotes by Martin Luther King Jr., Cesar Chavez, the Dalai Lama, Mahatma Gandhi, Robert Frost, Anne Frank, Mary Oliver and Walt Whitman. Accountable talk stems, such as “I believe, I think, I agree with,” are posted above my white board as conversational reminders to students. The bulletin boards display student work and current ideas or concepts being studied. A wood organizer in the far south-west corner houses felt-tip pens, rulers, glue sticks, colored pencils, crayons and construction paper for students to access.

When students enter my room, they can always find what we will be doing that day on the white board. I am a self-defined “organic teacher”. There is a flow to my classroom. I have never been comfortable with a prescribed routine, such as starting with Daily Oral Language, or another type of warm up. I generally begin class by greeting students, sometimes asking if anyone has something they would like to share, other times asking for a metaphorical weather report to get a feel for how individual students are doing, and what they might need help with, and then we pick up where we left off the day before. I almost always review what we did the day before and set a goal for where we are headed. I am a firm believer in backwards design and by the second month of school, alert students can generally make predictions of what will happen next instructionally based on how I have previously organized lessons. Students know that they are expected to write, discuss, share, listen, give feedback and revise their work in my class.

Unlike previous years where I taught a homogeneous group of students, the humanities core in which I conducted my research consisted of a diversity cluster. A cluster is a grouping of certified gifted and talented students and high achieving students who are not certified gifted and talented. Of the thirty-four students in my class, twelve were certified gifted and talented students. Four students were certified as English language learners, while another eleven spoke a language other than English at home, but had been reclassified as English language proficient. To get a snapshot of their abilities I looked at the previous year’s California Standards Test English language scores. Out of the thirty-four students, thirteen scored advanced, nine scored proficient and twelve students scored basic. Two of the students who scored advanced on the CST were English language learners. Two of the students who scored basic on the CST were gifted and talented certified.

Students received their class schedules on the first day of school and those who had never been scheduled into a cluster class before, but were now enrolled in mine never asked, “Why am I in a cluster class?” In fact, not one student ever brought it to my attention. The second week of school I did overhear one of my students, Mika, tell her friend, “You’re in a cluster class now, you’re going to have to think harder than that” to which they both smiled at each other.